As anyone who’s moved to a city sight unseen can tell you — this reporter included — making platonic connections isn’t easy. Adult friendships are fickle beasts in metros of millions, where casual friends are cheap currency.

Statistics back up my anecdotal evidence. According to a 2021 survey conducted by the Survey Center on American Life, an increasing number of people can’t identify a single person as a “close friend.” In 1990, only 3% of Americans said that they had no close friends, while in 2021, that percentage rose to 12%.

Many a startup has attempted to “solve socializing” with apps, algorithms and social nudges, or a combination of those three things. Bumble, for instance, has experimented with a communities feature that lets users connect with one another based on topics and interests. Patook took a Tinder-like approach to matching potential friends, using AI both to connect users and block flirtatious messages.

But not everyone’s found these experiences to be especially fulfilling.

“[I’m alarmed] by the tech industry’s lack of focus on building social products that are truly social rather than purely built to capture attention and exploit our desire for external validation,” Keyan Kazemian told TechCrunch in an interview. He’s one of the three co-founders of 222, a social events app that aims to — unlike many that’ve come before it — facilitate meaningful and authentic connections.

“Our society’s brightest minds — our fellow scientists, engineers and product managers — are being paid hundreds of thousands of dollars not to solve the existential problems of loneliness, climate change, space travel, cancer and aging but to instead find new ways to keep an already mentally ill society consuming endless content, always fighting for more of their attention,” Kazemian continued. “We’re building a product to swing the pendulum in the other direction.”

Kazemian co-launched 222 in late 2021 with Danial Hashemi and Arman Roshannai. They initially came together over a university-funded project around predicting social compatibility among a group of strangers. Toward the end of the pandemic, Kazemian, Hashemi and Roshannai — all Gen Zers (at 23, Kazemian is the oldest) — curated intimate dinners in Kazemian’s backyard over wine and pasta for friends of friends who’d never met each other, using machine learning and a psychological questionnaire to craft the guest lists.

“Folks loved the backyard dinners so much they convinced us to try to replicate it with real venues,” Kazemian said. “In early 2022, we moved to Los Angeles and started partnering with brick and mortar locations, creating a marketplace between hyperlocal venues and members looking to discover their city and meet new people through unique social experiences.”

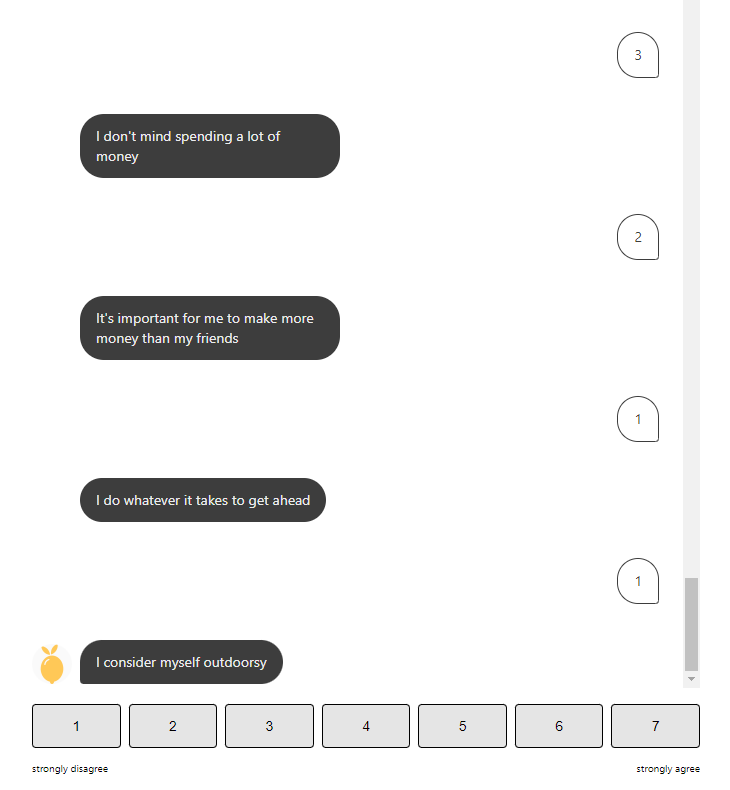

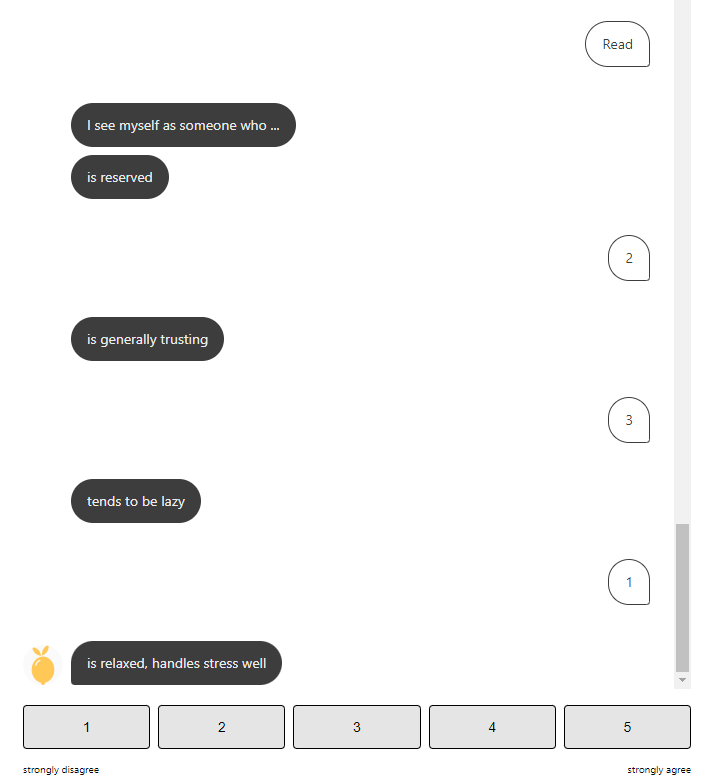

That marketplace became 222. Today, anyone between the ages of 18 and 27 can sign up for an account — the founding team is focused on the Gen Z crowd presently. There’s no app — just a basic Typeform workflow — and the sign-up process is designed to be simple. Once you provide your name, email address and date of birth, 222 has you answer roughly 30 Myers-Briggs-type questions covering topics from movie, music and cereal preferences to political views and religious affiliation.

222’s onboarding survey.

Some are uncomfortably personal — you’ll be asked about your income level, sexual orientation and college major — but Kazemian says it’s in the interest of narrowing down potential matches. “All of our data is encrypted and used only to better each 222 member’s social experience,” he added when asked about 222’s privacy practices.

222’s small print also indicates that data from the app is being analyzed as a part of a university social science project — a continuation of the one Kazemian, Hashemi and Roshannai led a year ago. Opting out requires contacting the company.

Image Credits: 222

After answering additional questions about your personality (e.g. “Is social activism is incredibly important for you?”, “Are you willing to have uncomfortable and difficult conversations with your friends?”) and go-to social activities (e.g. drinking, watching sports, going out to nightclubs), 222 has you list dietary restrictions and your ZIP code. You’re then asked to choose which factors you find most important in meeting new people (e.g., social scene, political leanings), and it’s finally off to the races.

Or it should be. When I tried to sign up, the website threw an internal server error. I eventually received a text confirming my enrollment, but it included a link to a webpage that endlessly loaded. Kazemian chalked it up to teething issues and promised a fix.

When the Typeform is working properly, Kazemian says, an algorithm behind the scenes factors in the answers to those 30-some questions to determine which of 16 categories your personality falls into. Once that’s decided, you’ll be notified if you’re selected for a 222 event — for example, dinner at a local venue partner of 222’s — which are currently held weekly and cost $2.22 to attend. Those who aren’t recruited for the dinner can choose to join for post-event mingling.

So is the algorithm any good? Kazemian asserts that it is, and that, furthermore, 222 is one of the few social apps directly training and matching based on real-life experiences.

“Most dating apps don’t do any sort of matching at all and rather focus solely on an Elo-type score, like in chess. Users on those products are only exposed to those that have a similar ‘yes-swipe-to-no-swipe ratio to themselves,” Kazemian said. “[By contrast,] based on our member’s onboarding questionnaire, 222 develops a psychological profile for each new sign up … Our algorithm will then not only pair each member with the best possible group of strangers for a given experience, it will also curate an itinerary for the evening with the best possible consumer experience — which speakeasy, café, concert or restaurant will this group of individuals have the best time at.”

That’s quite a claim to make considering Tinder and even Facebook has dabbled with helping strangers connect at events. But algorithmic robustness aside, users might be wary of attending events with perfect strangers. According to a 2022 report from the Australian Institute of Criminology, three in every four respondents had been subjected to real-life abuse through dating apps in the past five years.

222 isn’t a dating app, to be fair. And when asked about moderation and anti-harrassment measures, Kazemian said that the platform verifies every user’s identity — primarily through their payment information — and that venue staff are on hand at every event. Venue managers are educated on 222’s moderation and guidelines and it’s incumbent on them to instruct staff, Kazemian said.

“All 222 experiences are always in public and in a group setting, unlike most dating app meet-ups. 222’s phone number serves as an emergency hotline during experiences, so that members can text us if anything ever goes wrong and someone will respond right away,” Kazemian said. “Lastly, if any member is reported during a bad experience, that individual is immediately banned for life.”

222 is an intriguing platform, to be sure. But it’s tough to imagine it scaling far beyond its current size. The three-person company (222 plans to expand to eight people by the end of the year) has its hands full coordinating events in and around Los Angeles — its home city — at present, vetting venues and working to bulk up the backend infrastructure in preparation for an iOS app launch. There’s no revenue model (other than a merch store); unlike the now-defunct PartyWith, which shared a number of features in common with 222, 222 hasn’t experimented with sponsored events or other ways to monetize its experiences yet.

Perhaps that will change now that 222 has VC money behind it. Working out of the University of Southern California’s Viterbi Startup Garage, the company raised over $1.45 million in a pre-seed round led by General Catalyst with participation from backers including Y Combinator, 1517 Fund, Z Fellows, Crescent Fund and Wonder VC Scout Fund.

One wonders if the investor interest stems from the crop of new social and dating apps that aim to spark connections differently. A recent Crunchbase report highlights the growth of audio-based, video-based and even meme-based social apps, which have collectively raised tens of millions in capital from VCs over the past two years.

In an emailed statement, General Catalyst’s Nick Bonatsos expressed confidence in 222’s growth potential:

“Young people have been robbed of ~2 years of their social life due to the pandemic. They’ve been craving for social connection, making new friends and falling in love. The timing is ripe as 222 is offering their key audience a timely product — a marketplace facilitating chance social encounters at hyperlocal venues. At General Catalyst, we love partnering with Gen Z technical founders who are building products for themselves.”

Will 222 successfully turn the demand for social connection post-pandemic into a profitable business? That’ll depend on whether it can overcome the growing pains, technical and otherwise.

222 wants to match perfect strangers for bespoke, real-life experiences by Kyle Wiggers originally published on TechCrunch

DUOS