Many might recall how in the year 2000 Ghana found itself, for the sixth time in its history, unable to continue servicing its accumulated debts, accepted the tag of a ‘Highly Indebted Poor Country’ (HIPC), and underwent a series of reforms that ended in 2003.

As a result of the HIPC program, Ghana, between 2003 and 2006, became the second largest recipient of debt relief in Africa, which bonanza led to a fall in the proportion of government revenues spent servicing debt from roughly 40% to just above 10%.

Almost everyone also now knows that this massive fiscal room gave Ghana fresh latitude to explore new financing options. The country discovered the Eurobond market in 2007; and proceeded to build the Ghana Fixed Income Market (GFIM) in August 2015 to dramatically expand domestic borrowing.

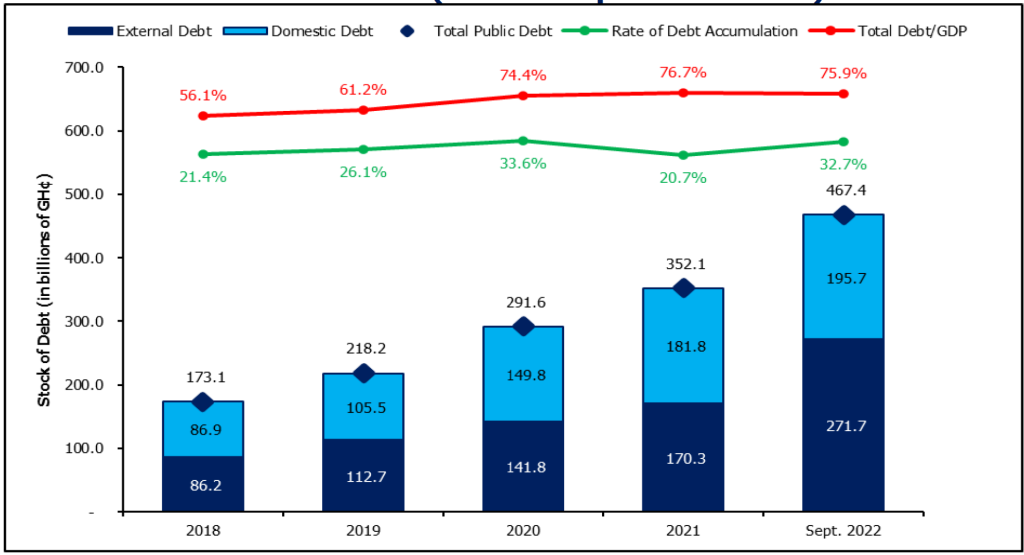

Unfortunately, the rate at which the country accumulated debt soon outstripped the rate of growth in national output and government revenue. Between 2018 and 2021, domestic debt alone grew, on average, more than 26% per year.

Foreign borrowing also expanded dramatically from 2018 onwards, resulting in Ghana’s outstanding Eurobond debt more than tripling in just 3 years. Indeed, annual foreign borrowing exceeded $6 billion per year until the taps were shut in late 2021, when the government failed to raise a $1.5 billion facility in October of that year.

That failure triggered a spiraling loss of market confidence as investors looked more closely at Ghana’s books and saw clear signs of pending insolvency. For instance, debt servicing costs had started to consume more than 50% of domestic tax revenue (today, it tops 70%). A selloff of Ghana’s bonds then followed leading to massive losses for investors, belated ratings downgrades, and an estrangement of Ghana from the international capital markets.

In July of 2022, the government reversed earlier decisions not to return to the IMF for a bailout and soon thereafter faced up to the unsustainability of public debt. In October 2022, it began to explore a restructuring of its debt, as a precondition for securing an IMF program, and formed a five-member committee of eminent bankers to solicit viewpoints from across the financial industry. Repeated claims were made about the government’s commitment to a “market-led” (not just “market-friendly”) process that will embrace the perspectives of the country’s key creditors.

Then, almost out of the blue, Finance Ministry mandarins met finance industry stakeholders on December 2nd 2022, and abruptly announced an imminent debt restructuringin which many creditors on the domestic front stood to lose more than 60% of the value of their government of Ghana securities (i.e. debt instruments, mostly bonds). Not only had no report by the 5-member committee been disclosed to any of the creditor groups, none of the proposals presented by the government on December 2nd reflected any of the perspectives and suggestions the industry representatives had shared with the committee.

On 5th December, the government formally launched the debt restructuring program and set a two-week deadline for creditors to sign away billions of Cedis of asset value. Industry players were not even expected to seriously consult with legal and financial advisors. Theirs was merely to acquiesce.

Yet, the financial effect of the government’s initial proposal was far bigger than any tax or other fiscal burden ever imposed on any Ghanaian sector in one fell swoop. Had the proposals been accepted in the form presented, the financial industry and other creditors would have forgone nearly 27 billion GHS in 2023 alone.

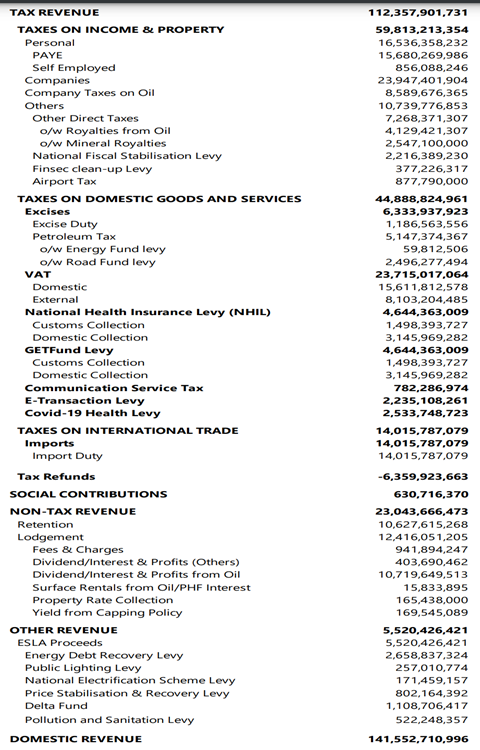

In comparison, the government expects to receive, in 2022, 12.1 billion GHS from oil and gas; 1.19 billion GHS from donor grants; 12.75 billion GHS from personal income tax; 16.5 billion GHS from corporate taxes (by the end of September 2022, the government had made less than 10 billion GHS of this target amount); 15.4 billion GHS from VAT (barely 10 billion GHS accrued by end-September); and 8.573 billion GHS from import duties.

The same picture plays out in 2023, as readers can see below; no tax handle generates anywhere close to the amount of resources the government intends to mobilise from domestic investors through the debt restructuring exercise.

The debt program therefore represents, undoubtedly, the largest single transfer of wealth from the Ghanaian private sector to the government in a single fiscal measure, in living memory. It is equivalent to doubling taxes on the entire corporate sector and giving the bill to only banks, insurance companies, pension funds and a few other investor categories to pay.

Whilst various exemptions since the original proposals were mooted have reduced the initial debt relief amount by some 15%, the “debt exchange” program still remains the biggest single domestic fiscal measure in the country’s history.

The least the government could have done before embarking on such a massive wealth transfer exercise was to have engaged closely with those whose wealth is being expropriated in the crafting of the overall program. This was not done. Instead, a fait accompli was presented to creditors.

Not surprising then to see the government postpone its unilateral deadlines twice, initially from 19th December to 30th December, and subsequently from 30th December to 16thJanuary 2023.

In the rest of this short essay, we discuss the 7 main stumbling blocks in the way of a smooth debt restructuring program.

- Poor Stakeholder Management

As already hinted above, the poor stakeholder consultations characterizing the Ghanaian government’s approach strikingly differentiate it from the approach adopted in many other countries where similar exercises have taken place in the recent past. In the case of Jamaica, to name but one example, the Advisory Committee representing the interests of the creditors had full access to all financial data underlying the government’s assumptions. It held regular engagements on a wide range of design issues to inform and shape the overall strategy. And it was seen to be articulating the full range of concerns shared by all major creditors.

The Ghanaian government’s idea of consultations is a couple of meetings where monologues are exchanged and vague reassurances of “support” given, this having been how it has conducted all matters of policy since coming to power in 2017. Unfortunately, in a debt restructuring exercise of this magnitude, where such massive amounts of money are involved, its usual style simply won’t cut it.

Creditors are instead demanding to co-create the program through a formal committee process. Creditors are furthermore demanding the engagement of top-notch financial and legal experts to serve this advisory committee, paid for by the government. Failure to accede to these demands would likely lead to more feet-dragging by the major institutions holding a very significant proportion of the debt, and by implication the failure of the exercise.

Considering the government’s incredible good luck in not facing any actual organized opposition to the entire IMF and/or debt restructuring program, it is mindboggling how it has still succeeded in bungling the process so far by failing to engage critical stakeholders in good faith. Given the general sense of resignation across all factions of elite society about the inevitability of some kind of debt restructuring to salvage the economic situation, the government’s inability to build a strong national consensus around the measures needed for the recovery betrays a woeful lack of leadership.

Domestic investors may take some cold comfort from the fact that the government has not limited this practice to the home front. It announced a freeze on servicing external debt without bothering with the niceties of applying for consent from its foreign creditors.

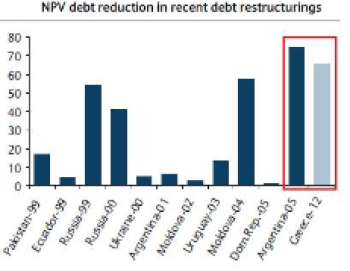

It is true that there was no assurance that a “consent solicitation” of this nature would have been automatically granted. Zambia learnt that hard lesson in 2020. However, research shows that countries that default on their debt before initiating the restructuring process, as Ghana has done on the external front, tend to inflict greater losses on investors. This was the case in Russia in 2000 (50% NPV losses) and Argentina in 2005 (75% NPV losses), for instance.

By contrast, in situations where countries default only after the formal restructuring engagement has commenced, like Pakistan in 1998, Dominican Republic in 2005, and Uruguay in 2003, investors tend to face relatively lower losses (less than 5% NPV losses in the case of the Dominican Republic, for instance). Ghana’s decision to freeze debt servicing before prior consultations have, therefore, signalled an intent to be aggressive in the upcoming negotiations and to be dismissive of investor anxieties. Such vibes, unfortunately, could delay the reaching of an amicable settlement with foreign investors, thereby slowing the consummation of the provisional IMF deal announced on 13th December in the government’s preferred timeline of the 1st quarter of 2023.

It bears mentioning that the Ghanaian government’s timeline of weeks for the conclusion of the debt restructuring process, though not completely unrealistic, is highly optimistic.

Lebanon has been working on its restructuring program since early 2020; Zambia since late 2020; and Suriname since mid-2020. Belize needed 15 months to complete a homegrown program with only technical input, and no direct financial support, from the IMF.

Of course, there are also more encouraging episodes like Ecuador’s that took just 4 months to conclude (in the heat of the pandemic) and, also, the case of Argentina which required 5 months. Instructively, analysts have highlighted the sharp contrast between the Argentinian and Ecuadorian approaches; The latter did not allow a focus on haste to damage investor relations and thus obtained more quality concessions without the acrimony that characterised the Argentinian process.

However one looks at it, Ghana’s attempt to ram through the entire process in barely 3 weeks without even a formal creditor coordinating mechanism is somewhat unprecedented. A case can be made that haste is getting in the way of prudence.

2. Effective Burden-Sharing

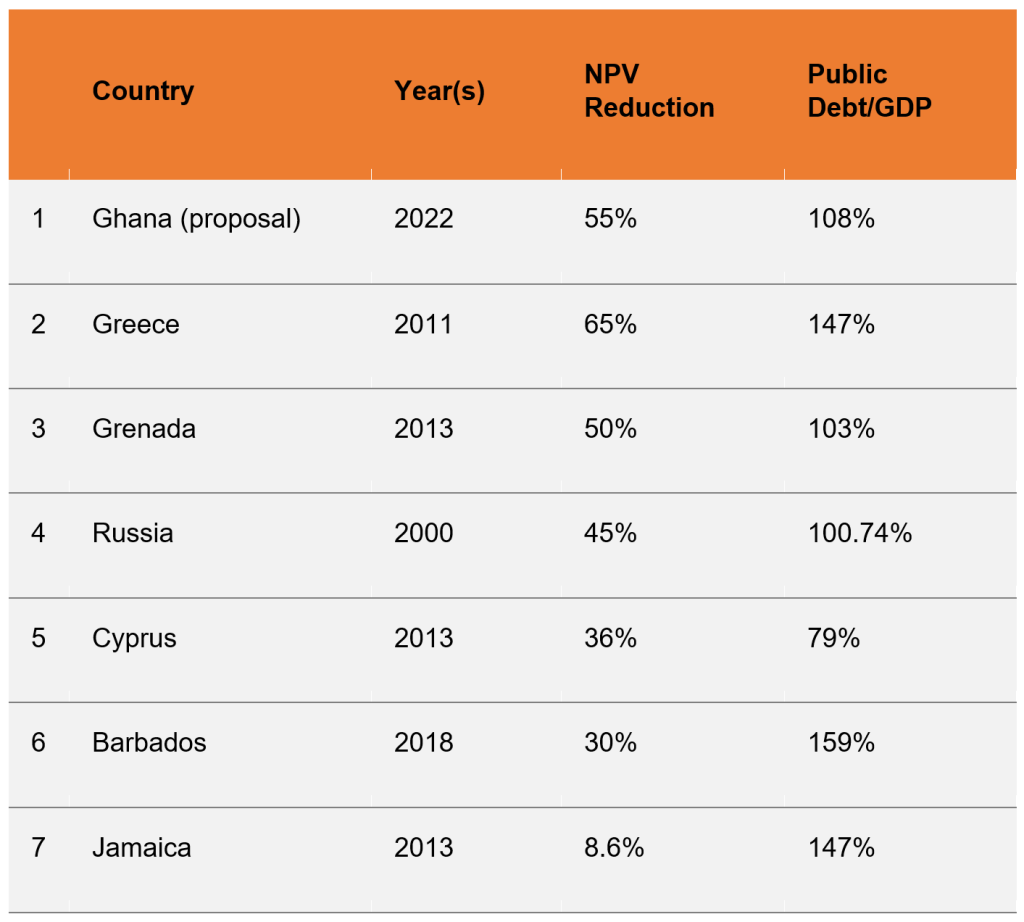

Data from the IMF, Barclays Capital, and others on comparative debt relief levels recorded in various debt restructuring programs around the world reveal a worrying feature of Ghana’s debt crisis response plan: the government wants to shift too much of the common pain to investors.

More than a few international analysts are complaining that the amount of government debt burden reduction being sought by Ghana relative to its overall public debt is considerably higher than was witnessed in many previous debt restructuring episodes around the world.

Such a belief tends to quickly degenerate into suspicion that the debtor government is being strategic rather than fair and accommodating. Ghana’s behaviour is slowly beginning to resemble that of Greece during its 2011/2012 default episode, which eventually descended into legal squabbles and litigation.

Research by Moody’s shows that investors these days have, since 2015, become used to recovering on average more than 63% of the value of their investments during sovereign debt defaults instead of the 52% average recovery rate seen since 1983. The recovery rate in Ghana’s domestic exercise is lower than 45% for many creditors. The country’s unilateral debt service freeze signals for some analysts prospects of similar steep losses for external creditors too.

There is no doubt that investors have to take a major hit. They are better positioned to absorb financial losses than ordinary Ghanaian citizens are to suffer cuts in social services. But the government is even better placed to bear the mere political costs of cutting patronage spending and wasteful perks.

3. Credibility of the Fiscal Adjustment Strategy

Sovereign creditors get jittery from any sign that the sovereign debtor (Ghana in this case) is not willing to absorb its fair share of the harsh adjustments needed to balance the books and restore fiscal stability and macroeconomic health. Ghana’s seeming overreliance on debt relief and tax raises, and the authorities’ reticence in cutting expenditure by trimming wanton waste identified by many fiscal activists, appear to be steadily giving credence to such a suspicion.

Researchers, such as Veronique de Rugy and Jack Salmon, have shown however that fiscal adjustment programs that balance tax raises more robustly with meaningful expenditure cuts succeed 55% of the time versus only 38% for those that rely predominantly on tax raises.

Creditors worry about the credibility of the overall fiscal adjustment plan because they hate to be bitten twice. Supposing they give in to Ghana’s demands and accept the massive losses being proposed on the basis that half a loaf is better than none. If Ghana’s fiscal strategy turns out to be poor, they may end up losing the other half of the loaf should Ghana default again or start to show signs of future insolvency and the value of the already devalued debt they hold depress further.

The historical evidence does suggest that once a country has defaulted once, the prospects of a future default does go up, and, according to Tamon Asonuma, a subset of countries, about 24 or so of them being frontier economies, tend to default serially. On average, such countries have defaulted more than 4 times each at intervals of just a little over 3 years.

Thus, without considerable assurance about the fiscal consolidation strategy being pursued by the government, restructuring negotiations could drag out for months, as has been the case elsewhere.

4. Absence of Credit Enhancements in Exchange Instruments

Modern creditors have become used to receiving perks when sovereign debtors want debt relief through the exchange of new instruments for old. The new instruments can be enhanced in various ways to make up for the upfront losses. For example, when Seychelles defaulted in 2010 the new debt instruments it tendered to investors had a fresh guarantee backed by the African Development Bank (similar to how the US Treasury backed the “Brady Bonds” used in resolving the 1980s Latin America debt crisis). Even hard-handed Greece offered exchange notes that had English law protection to replace the old bonds that had less-valued domestic law protection. Russia, in a similar vein, added Eurobond features to its replacement bonds in 2000 in order to placate bond investors.

Ghana, by contrast, is pushing to insert single-limb collective action clauses into the new bonds that would make future defaults easier (because, unlike the case at present, a vote by a majority of creditors will impact all creditors). It is removing English law protection from the ESLA and Templeton bonds. And it is applying a total interest standstill that should all but eliminate tradeability of the new bonds in 2023 (an approach that demolishes the prospect of the new bonds providing the liquidity to satisfy redemption that some fund managers claim to be anticipating).

In short, the new lower-value bonds the government of Ghana is offering investors to replace their existing government bonds not only lack attractive enhancements, but they are also manifestly of lower quality in other respects too.

Everyone agrees with the general principle of debt restructuring leading to real liquidity relief and thus providing the government with fiscal room to reset the economy on a better trajectory of sustainable growth. The issue is one of fairness. Investors were actively courted to inject funds that made the government look good. If things have taken a turn for the worse, they can’t be milked twice to make the government’s life easy.

5. Lack of Legislative Guardrails

Much has been made of an advisory opinion by Ghana’s Attorney General suggesting that laws cannot be made to retrospectively attack the rights of creditors and that any such laws would be unconstitutional.

But this advice was quite pointless as that much has always been obvious. In the Greek debt default episode (2011 – 2012), which has become a benchmark of some sort, similar issues were exhaustively addressed. Eventually the statutes that were specially made for the occasion provided a kind of framework for government bankruptcy proceedings in relation to the voting mechanisms required to allow orderly resolution. They were not necessarily expropriation tools.

An example closer to home would be the 2016 law used to resolve Ghanaian banks, several of whom were founded before the law the passed. It would have been preposterous for anyone to argue that the law was being applied “retrospectively” to dispossess bank owners.

The simple fact of the current situation is that the government of Ghana needs to undergo some kind of bankruptcy process. The country is in completely uncharted waters. Rights and obligations are being improvised on the go. It helps to have laws passed on a bipartisan basis to clarify some of the grey areas and to elevate the weightiness of these momentous developments. To leave everything to the administrative fiat of the Finance Ministry is to seriously underestimate the scope of the crisis and its sociopolitical implications going forward.

6. Upside Sharing & Downside Mitigation

Because all debt restructuring programs are undertaken based on forward-looking assumptions, considerable uncertainty is usually a constraint on the calculations of the parties. For example, the government-debtor in making the case of its inability to service debts going forward does so based on macroeconomic projections several years into the future. But some of the anticipated trends could pan out differently. Growth may be higher, interest rates may rise, and inflation may stay stubbornly high.

The true value of the new bonds given to investors in place of their original holdings could thus fluctuate wildly based on how the macroeconomic winds blow. A government that anticipates hardship some years down the line could instead experience a commodity boom that dramatically transforms its finances. Or an influx of massive Chinese investment could change the original trajectory of public borrowing requirements. Or something else.

Moreover, some aspects of any economic improvement may well come from the fiscal room created by the debt restructuring and would in that sense have been partly paid for by investors.

Investors would hate to make massive sacrifices for the long-term only for the situation to abruptly improve and all the gains accrue to the government counterparty. Whilst this is not an easy concern to accommodate, the rise of contingency instruments has revamped the legal technologies available in crafting strategic options for both the government and its creditors to equitably share any windfalls or upside. Argentina in both 2005 and 2010, Ukraine in 2015, and Greece in 2012, all utilised so-called “GDP warrants” to offer investors assurance of higher earnings should the economy grow faster than the baseline. Grenada in 2015 tied its warrant offers to growth in government revenue, which is harder to game.

In a similar vein, some investors have sought protection from a worsening downturn that could exacerbate inflationary and interest rate conditions, whilst some government-debtors have sought to add additional cover for natural catastrophes and other severe reversals of fortune.

Ghana’s current proposals offer none of these creative possibilities. Perhaps it is time to think up one or two gaming-proof mechanisms.

7. Narrative Consistency

A sovereign debt default is a wealth destruction event of megaton proportions. In the panic, paranoia breeds. In such an environment, nothing muddies the waters like inconsistent messaging from the defaulting sovereign.

A. It started with the president and various of his assigns promising investors that there will be “no haircuts”. And then proceeding to unveil a debt exchange program with stiff haircuts. Current domestic bonds maturing, on average, within 3 years will be replaced with a new set maturing on average in more than 10 years. Coupon rates have been cut from an average of more than 20% down to an average of less than 10%. The only way to preserve the value of a bond after such heavy reprofiling (and thus avoid the equivalence of a principal haircut) would have been to increase coupon rates in latter years. Despite near-consensus among investors that there have been haircuts, government spin-doctors continue to persist in the false “no haircuts” narrative.

B. The government has made significant political capital from the decision to exclude treasury bills by presenting it as a gesture of compassion towards the many ordinary citizens who save through these instruments. The real reason of course is that with the bond market having collapsed, and the Eurobond market shut to Ghana, the only public financing lifeline available to the government is the treasury bill market. Some investors were thus surprised to see a caveat in the original exchange agreement hinting at the possible future inclusion of treasury bills in the exchange program.

C. Similar discrepancies between rhetoric and action can also be seen in the decision to abandon the earlier pledge to co-create the debt restructuring program with local creditors and the total reliance on foreign advisors and consultants when the actual process got underway.

It would be vitally important going forward that such twists and turns in the official narrative stop for the good of the program.

Conclusion: More Carrots than Sticks

On 24th December, the Ghanaian authorities announced a new deadline for the debt restructuring program of 16th January 2023. The announcement is the first acknowledgement that the government is beginning to take the concerns of creditors seriously.

In the new proposal, the authorities have increased the number of new instruments intended to replace the 69 extant bonds they are seeking to retire from 4 to 12. They also seem to have walked back on an earlier strategy to exempt non-institutional bondholders en masse. Coming on the back of a decision to exempt pension funds from the exercise, the revocation of the exemption for non-institutional bondholders has been interpreted variously as a shortfall-plugging mechanism and/or as an attempt to seal a loophole that would have allowed institutional holders to enjoy an exemption by transferring holdings to individuals and masking ultimate corporate beneficial shareholders through offshore trusts.

The new proposal, whilst showing capacity for flexibility, still falls short of the co-creation demands being made by creditors. It is not clear why the government prefers to engage with creditors without a coordinating mechanism such as a formal advisory committee representing the bulk of outstanding debt. Perhaps it fears that such a process might undermine its negotiation position by removing the “divide and conquer” option. The danger with the attempt to preserve the fragmentation of the creditor community is the likelihood of inertia being traded for lack of organised resistance.

At any rate, there are hints of external holders of domestic debt making preparations to litigate. A group holding derivatives that expose them to defaults on the underlying government of Ghana securities has already filed for an advisory opinion on whether Ghana is already in default.

With nearly 50% of domestic debt likely to fall under one or the other exemption even before formal, coordinated, negotiations, the government is watching in slow motion as bits and pieces of the estimated 22.5 billion GHS in possible liquidity relief for 2023 from the debt exercise start to vapourise.

It is natural in these circumstances for the Finance Ministry to harden its resolve and try and hold the line without further concessions. But such an approach would do little to deter holdouts. The leaked attorney general report has revealed major chinks in the government’s legal armor: there is very limited prospect that holdouts will get a worse deal from the Ghanaian courts. And given the one-year moratorium on interest payments affecting all creditors, the time delay penalty – stemming from litigation – is less onerous for holdouts if government chooses to outrightly default on their bonds.

The Finance Ministry has threatened to render old domestic bonds essentially useless by making it difficult for them to be treated as banking assets. But such threats seem foolhardy when the government’s number one risk management concern in this entire exercise is maintaining financial sector stability, for which cause it is even willing to relax prudential regulations.

There are further logistical complications stemming from the decision to allow exemptees like pension funds to enjoy the full value of old bonds, which presumably means the ability to trade them. Trying to implement elaborate rules on the GFIM trading platforms, including the CSD settlement system, to discriminate against certain old bonds could lead to serious confusion, and would at any rate take time as international contractors and IP owners are involved in managing the platform. And should holdouts exceed 40%, the logistical issues will merely compound.

In a previous essay we pointed out how certain holders of government debt, like insurance companies, operate in a sensitive market such that any attempt by the government to selectively default on their holdings would trigger various other contagion effects. Similar to the banks, it is not in the government’s interest to take actions that could destabilise insurance companies due to the sensitive intermediation roles they play within the financial system.

All told, therefore, the authorities have very few sticks to coerce the kind of rapid capitulation they have been hoping for since the onset of the debt restructuring program. What they have going for them is the widespread convergence across the entire society on the view that debt restructuring is inevitable. The government should not squander this real benefit. Rather, it should look carefully at its stock of less expensive carrots and leverage them to the hilt. Most of its cards centre around the engineering of consensus by giving creditor groups the sense of truly being part of the solution rather than the problem. A time-bound co-creation process, supported by the industry’s preferred expert modellers, may be far less costly and program-derailing than the government fears. In fact, if designed effectively, it may even save time and considerably nudge the participation rate towards the highly optimistic 80% target the Finance Ministry has now set itself.

The government would do well to move decisively in addressing at least some of the issues raised in this essay well before the 16th January 2023 deadline. If by then teething issues still remain, it would be wise not to announce another new unilateral deadline. Whatever announcements it makes from here on out should be done with the full acquiescence of the leadership of the key creditor groups in a show of collective purpose.

Such optics are hugely critical in dispensing with the image of high-handed fiat the government’s tactics have to date painted. And, even more critically, they are needed to salvage what credibility remains in the government’s ability to steer a successful debt restructuring program and progress from there to successfully launch the new IMF deal.