Italy’s highest-profile mafia target only tells us where to find him 20 minutes before we meet. Nicola Gratteri, the prosecutor leading the country’s fight against organised crime, has learnt to live in constant danger – and too much advance warning leaves him exposed.

We are instructed to wait for him outside the court in the southern region of Calabria where he is overseeing the biggest trial of its kind since the 1980s. More than 330 suspects have been testifying there and 70 of them have already been convicted.

Suddenly Gratteri sweeps in, surrounded by his escort of five police cars. We thank him, a few times, for his readiness to meet and talk. “Stop thanking me – and let’s get on with it,” he snaps. “There’s nothing I hate more than dead time.”

The man on the kill list of Italy’s most powerful mafia, the ‘Ndrangheta, who has devoted his entire career to taking on the group, does not do pleasantries.

And then he decides to drive us to his office 40 minutes away. He will be freer to talk there. We climb into his bullet-proof car and so begins perhaps Italy’s most dangerous commute.

“I’ve been living with this level of security since 1989, when my fiancee’s house was shot at, and someone phoned her in the night to tell her she was marrying a dead man,” he recalls. “It’s escalated to reach this suffocating level of control.”

There is no alternative, given what happened 30 years ago. In 1992, prosecutor Giovanni Falcone was blown up by a bomb planted beneath a motorway near Palermo by the Sicilian mafia, Cosa Nostra. It killed him, his wife and three police officers. His colleague Paolo Borsellino was assassinated by a car bomb two months later.

Their murders – and the searing images of the half-collapsed motorway at the scene of the Falcone attack – are still seen by Italians as a defining moment in their modern history. The magistrates are revered for their heroism and the brutality of the crimes remain a potent symbol of the mafia’s capacity for terror.

With his eyes on the road, Gratteri tells me he thinks of the murdered judges often – and how they, too, were moving targets as they drove through another part of the country poisoned by organised crime. “I often talk to death, because you have to rationalise fear in order to move on,” he says. “Otherwise, I couldn’t do this job.”

We speed across the rugged and lush toe of Italy: the bastion of the ‘Ndrangheta since its origins in the 19th Century. The criminal syndicate is based around family clans, or ‘ndrine, who traditionally controlled the mountain-top villages of the Calabrian landscape, their die-hard loyalty forged by blood ties.

While Sicily’s Cosa Nostra and the Camorra around Naples are better known internationally, in part through their dramatic mass bombings, both have been weakened by a relentless police crackdown. As a result, the ‘Ndrangheta has risen in their place and is now Italy’s most potent mafia, with offshoots around the world, from South America to Australia, and an estimated annual turnover of around $60bn (£49bn).

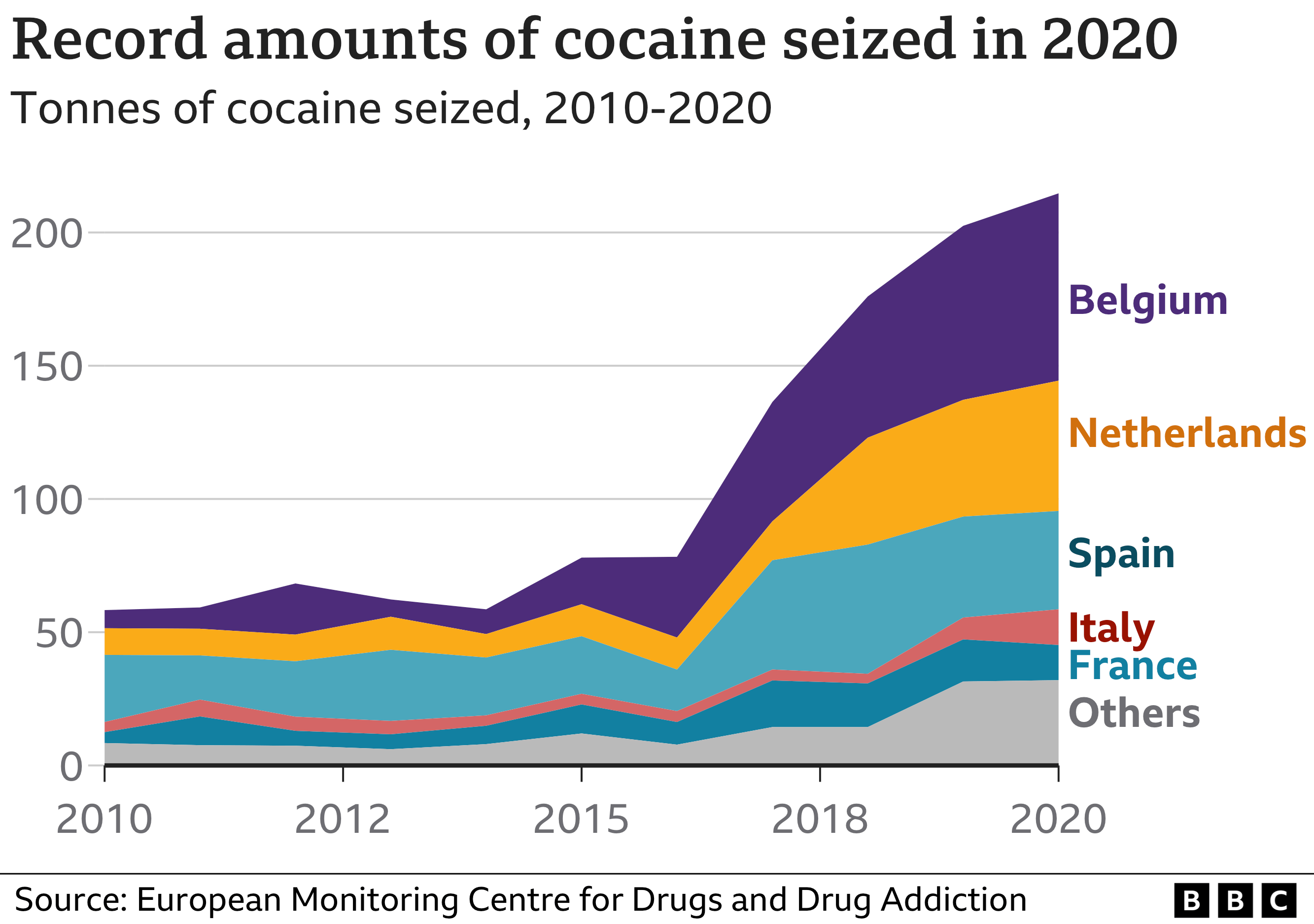

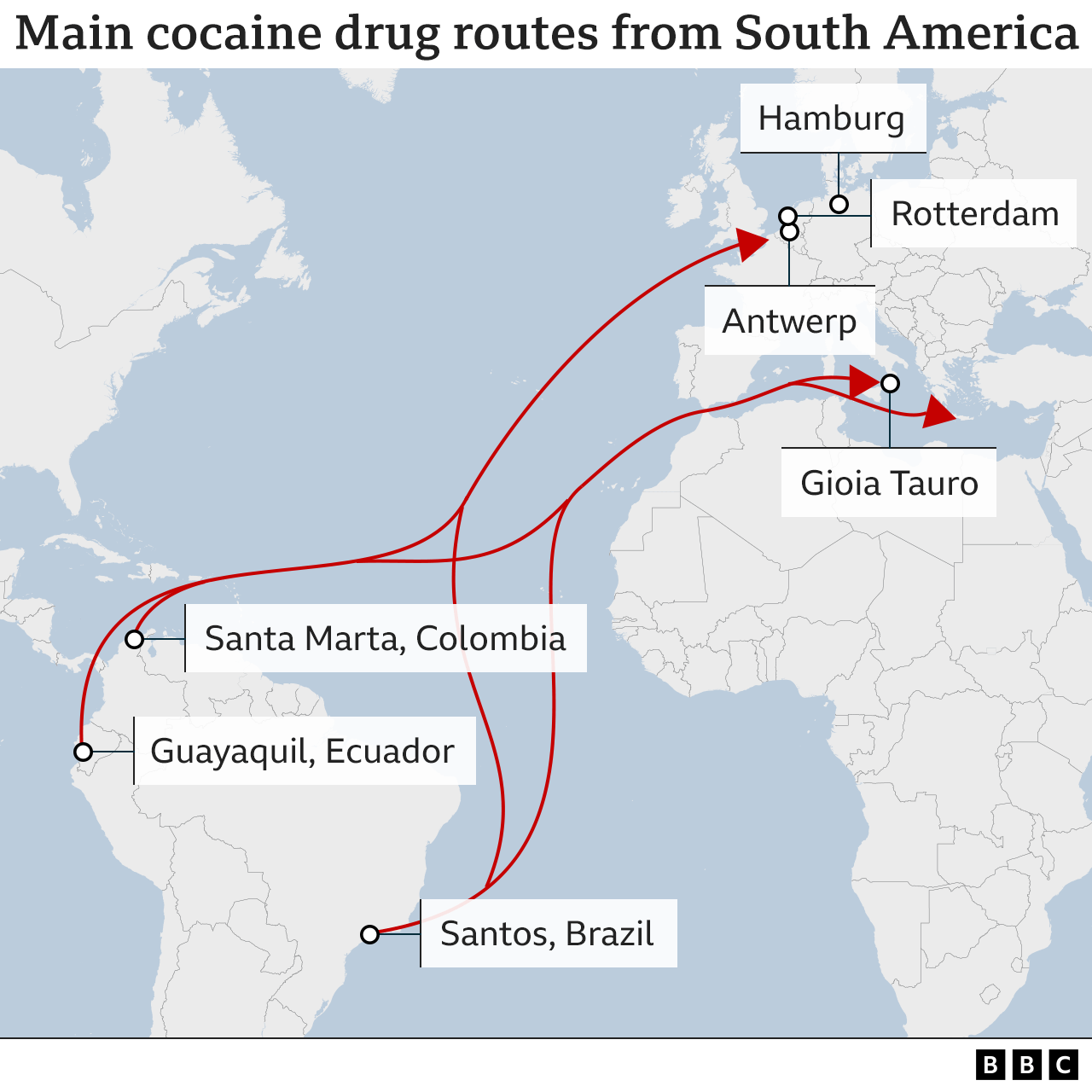

Their currency is cocaine. The group dominates the global market and is now thought to control up to 80% of Europe’s trade in the drug.

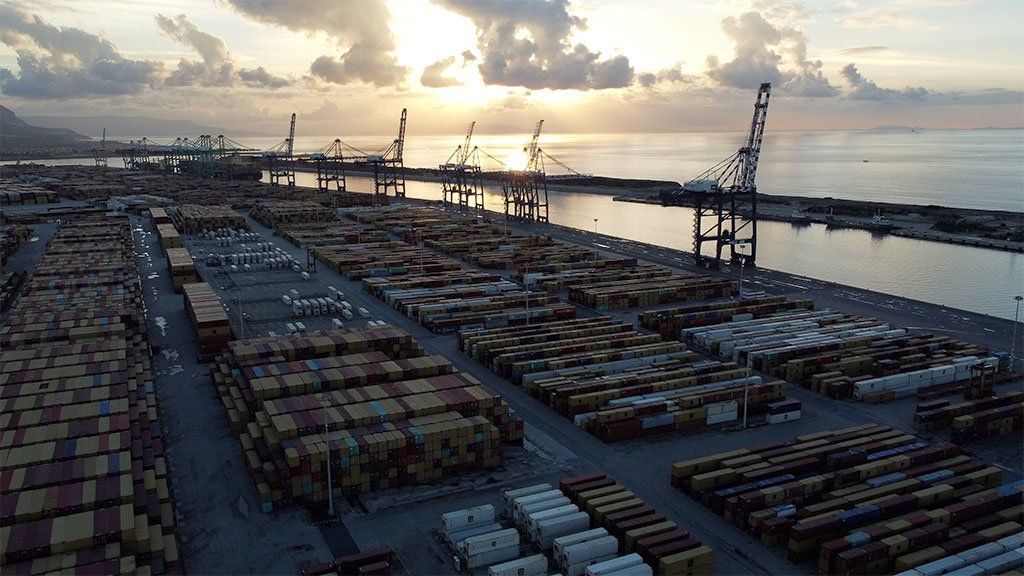

Most is funnelled through Gioia Tauro, Italy’s busiest container port, a hulking facility in the south of Calabria. A fraction of the cocaine that arrives here is for the Italian market, with the rest passing through and onwards east, to the Balkans and the Black Sea. Military hardware bound for Russia has also been intercepted here.

We watch as a freshly arrived container carrying bananas from Ecuador is checked, first by sniffer dogs and then by officers from the Guardia di Finanza, or financial crime squad, who cut open boxes to rifle through the bunches of fruit. This shipment is clean – but many others are not, with the quantity of cocaine impounded here almost tripling in the past two years.

A recent police operation swooped on port workers suspected of being involved in a massive ‘Ndrangheta trafficking ring. Thirty-five were arrested and seven tons of cocaine, with a street value of $1.4bn (£1.14bn), were seized.

We are given rare access to see the bulk of these drugs, which sit in a locked cell: hundreds of tightly wrapped packets that are photographed and then analysed.

A fragment of the white powder is cut away and placed into a tube containing a liquid solution, which is squeezed into testing kits that look like something from the pandemic – only this time detecting crime, not Covid. After a few seconds, a red line appears. It’s positive, with a purity of 98%.

The cocaine seized by the Guardia di Finanza at Gioia Tauro port over the past two years accounts for more than half of their entire haul from the last two decades. ‘Ndrangheta smuggling may be going up, but so too is police know-how, with forces collaborating across borders.

A massive international operation in 2019 by officers in Italy, Germany, Switzerland, and Bulgaria led to the arrests of 335 suspects, including lawyers, accountants and an ex-MP. All were part of, or linked to, the Mancuso family – one of the estimated 150 ruthless clans that make up the ‘Ndrangheta.

In the aftermath of this, the biggest blow to the group in its history, the so-called “maxi trial” in Calabria began two years ago. A call centre on the outskirts of Lamezia Terme was converted into a space large enough for some 600 lawyers and 900 witnesses, many testifying by video link. Charges include murder, extortion and drug-trafficking. More than 70 have already been sentenced.

Sitting inside the enormous room, with cages set up on the side, it feels like the visual symbolism is important here: a set-up designed to show Italians that their state is hitting the ‘Ndrangheta and that the mobsters are not untouchable.

It is the biggest trial of Nicola Gratteri’s career. As we are whisked into his office, with his close-protection team always one step behind, he tells me the arrests deprived the ‘Ndrangheta of 70% of their control in Vibo Valentia, one of their stronghold provinces.

“If they are all convicted, it means breathing space for the community,” he says. The Mancusos, though, are just one, albeit powerful, family of the ‘Ndrangheta and this is by no means the beginning of its end. “As soon as I finish this trial, I’ll be moving on to another,” the prosecutor adds.

He has dedicated – even sacrificed – his life to this struggle. “I don’t have a life,” he tells me. “To go into a cafe, we have to stop and discuss it with my protection team. Someone enters to pay and then we go in and drink the coffee. We have to stop and discuss where to use the bathroom. I haven’t gone to a cinema or a restaurant in 25 years. My barber comes here to the office when I need a haircut. I hardly ever see my family. But inside my head, I’m a free man.”

I ask if it’s worth it. He sighs heavily. “It’s worth it if you believe in it – and I do,” he replies. “I believe I’m doing something important. There are thousands of people who believe in me and for whom I am the last resort, the last hope of change. I can’t disappoint them.”

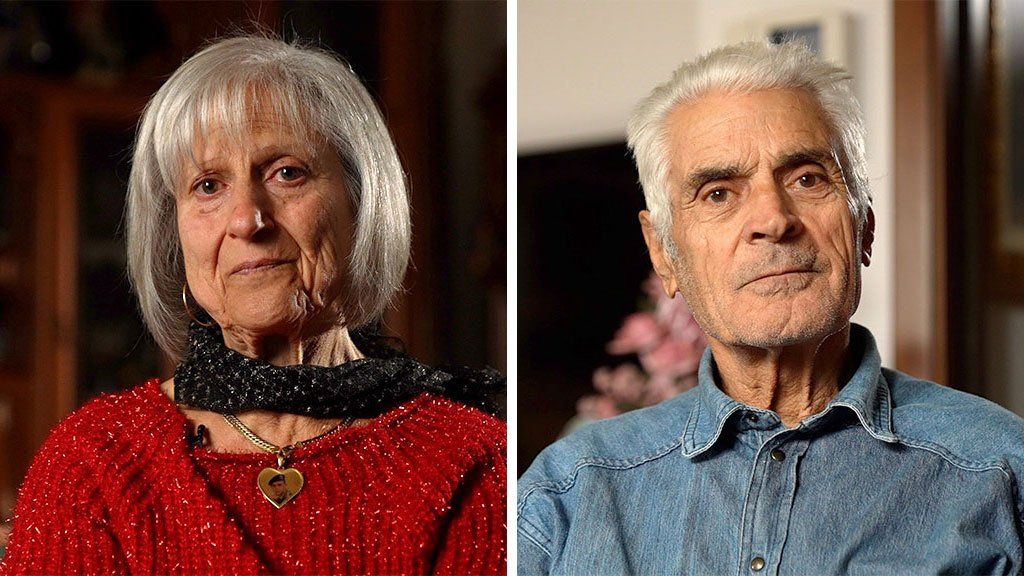

Sara Scarpulla and her husband Francesco are among them. In 2018, they endured the unimaginable, when they buried their only child, Matteo, blown up by a bomb planted on the undercarriage of his car.

His assassins were alleged to have belonged to the Mancusos, the ‘Ndrangheta clan currently on trial, who had targeted Matteo and Francesco after a prolonged dispute over the boundary between each other’s land.

At the cemetery in the town of Limbadi, just metres from the grave of Matteo, lies the Mancuso family tomb: the victim and the relatives of his killers almost side-by-side in a region soaked in its blood feuds.

In their living room, where the walls are adorned with giant photographs of Matteo, Sara tells me he was “the joy of life – polite and exceptional. I’m proud to have been Matteo’s mother and proud to have had him as a son”.

Sitting beside her, Francesco, who was in the car with Matteo at the time, distractedly taps on the table, watching helplessly as his wife can no longer hold back the tears.

“Ours is not a life anymore,” she says. “Sometimes, I ask God: ‘Where were you when Matteo was dying?’ And Matteo’s girlfriend tells me: ‘He was there, taking Matteo with him’”.

Limbadi, Sara says, is riddled with the ‘Ndrangheta. They control local businesses, hold the levers of power and inspire fear with their thuggish behaviour. As her land dispute with them escalated, she recalls how they would kill her family’s animals and then throw beheaded chickens on to the roof of her house.

“Until the mentality of people changes, things will never change,” she adds. “We have to plant the seed of change, like Prosecutor Gratteri and all prosecutors like him. Until we follow in the footsteps of these people, we will be stuck here with the ‘Ndrangheta in charge.”

A look of defiance suddenly takes hold. “I need to fight, to go the front line and shout in the streets of this town: ‘The ‘Ndrangheta must leave from here!’ This is not the ‘Ndrangheta’s town. It is Matteo’s town.”

But prising apart the ‘Ndrangheta’s suffocating grip will require more than a change in mentality: it will need the mafiosos to turn against the mafia, breaking the “omertà”, or code of silence.

There are, though, precious few turncoats among a group founded on blood ties, in which disloyalty means betraying your own family.

We track down one, Luigi Bonaventura, who is testifying in the Mancuso trial. He agrees to meet in northern Italy, somewhere not far from where he lives, though he will not tell us exactly where that is. His testimony offers a rare insight into the inner workings of the mobsters and how their indoctrination functions.

Sixteen years ago, he began collaborating with police – in order, he says, to give his children the freedom that he never had and has lived under witness protection ever since. He uses his own name but covers his face with a balaclava, so as not be recognised by those he turned against.

“The ‘Ndrangheta is a tribe, and if you are born into that family while it is at war, you can do nothing but grow up with the incitement to hatred and violence,” he tells me. “The words repeated were always the same: ‘Kill, kill, kill’”.

He recalls being brought up “as a child soldier”, handed a gun aged 10 and playing with real weapons as if they were toys. Having been trained as what he calls “a sleeper-cell killer”, he was called to fight at 19 when his family went to war with another. “I was involved in five murders,” he says. “Three I witnessed, and two I carried out.”

He claims his collaboration has led to the conviction or arrest of more than 500 ‘Ndrangheta suspects. What impact, I ask, does he think the ongoing “maxi trial” will have on the mafia?

“The ‘Ndrangheta does not have one head, it is not Sicily’s Cosa Nostra, with a boss of bosses who, once he collapses, brings everything down with him,” he replies. “The ‘Ndrangheta is a monster, a multi-headed hydra, and if one is cut off, there are many others. It’s a matter of time, maybe 10 years, but the Mancuso clan will regroup, and they will be back stronger than ever.”

It is a pessimistic prognosis. But on the ground in Calabria, anti-mafia associations are working to educate the next generation and ensure Italy’s young are steered away from the clutches of organised crime.

However, the mafia’s tentacles are so long, its infiltration of Italian society so deep, that even Nicola Gratteri, the country’s top authority on the ‘Ndrangheta, tells me Italy will never be free of its grasp. “It can be reduced a lot, but it would take a revolution to fight it. We still need a stronger system – and above all, we need to invest in education and culture.”

That, he says, is what made the difference for him as a boy, while many of his childhood friends were ensnared by the ‘Ndrangheta.

“If I’d been born a hundred metres down the road, I would have been a mafia boss today,” he remarks. “But I was lucky because I was born into a family of honest people. Many of my classmates have been killed with a sawn-off shotgun; others I have had arrested for weapons or drugs.”

He recalls being deployed to Miami when a former school friend was arrested with 800kg of cocaine on his sailing ship. “He told me he had ruined his life. I said to him: look, you can still change things, there’s a chance to cooperate, but he refused.”

In this battle for the soul of Italy, I ask which side is winning: the mafia or the state? He smiles. “It’s a draw. To win, we need to change the rules of the game, with a prison system strong enough to discourage the criminals.”

Hero to many, enemy of some, Gratteri seems somehow an isolated figure, unafraid to pick fights and unturn stones at the highest level. So does the 64-year-old have regrets?

“No,” he replies. “Maybe I could have done more – even if it was not humanly possible. I’ve done the best job in the world – and I’ll go on as long as I can.”

He pauses, collecting his thoughts. “Everything in life has a price, no? To have had a normal life, I would have had to go slower. Perhaps I’d have had to work less. But I’d have felt like a coward. And living like a coward makes no sense to me.”

As we draw our time with him to a close, he checks his phone. “Pack up quickly,” he instructs us, “and move your bags out, I need to lock up here and go.” With a brisk handshake, the anti-mafia crusader is off to fight his next battle.