It was a day when people stood still – on the streets and in their homes – to witness Queen Elizabeth II’s final journey.

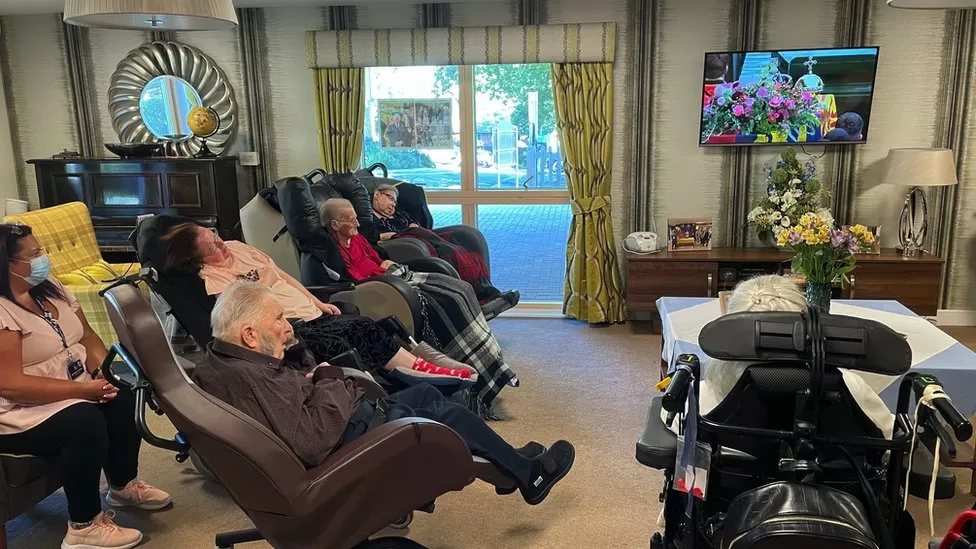

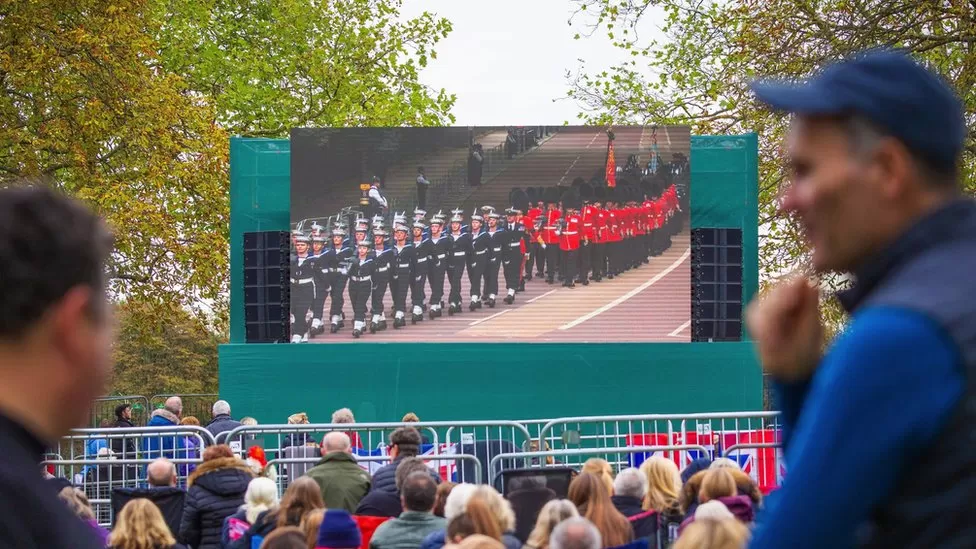

Royals and world leaders were inside Westminster Abbey. But outside there were many more, ordinary mourners lining the streets of central London. And further beyond – in living rooms and parks, in pubs, cinemas and town squares – the British public marked the first state funeral for nearly six decades in millions of individual ways.

In Doncaster, Alistair Mitchell brought afternoon tea and sandwiches for his mother, who had not been able to make the journey to London. At the Curzon cinema in Sheffield, there were no pre-show trailers, or the sound of rustling popcorn – just an audience dressed mostly in black as they watched the ceremony. Blackpool’s illuminations were switched off.

At 06:32 BST, the final mourner filed past the Queen’s coffin at Westminster Hall as her four-and-a-half-day lying-in-state drew to a close. The Queue had come to end. But overnight, Monday’s crowd was already gathering. At Horse Guards Parade, it was 10-people deep before 08:30. By 09:10, viewing areas for the procession route were full.

At The Mall, the Rowlassons – Kyre, 23, his mum Beveley, 41, and granddad Fred, 72 – had secured a front-row spot, after setting off from Birmingham the previous day. All three had spent the night on the ground in their sleeping bags. Had they slept? “Not a wink,” says Kyre.

And then, at 10:44, the Queen’s coffin began its short journey to Westminster Abbey.

As she went to switch on her television, Liz Perry, 59, was struck by the silence outside her living room, in Derby. It was, Liz thought, as if a blanket had been draped over the entire street – clearly, all her neighbours were tuning in too.

At St Anne’s Church, in Bishop Auckland, County Durham, Sue Lalor had taken her seat in a pew. A screen above the altar was showing the service. Sue could have watched at home but that would have meant doing so alone. “This was a moment I wanted to share with other people,” she said.

Not everyone in the country has been as caught up in the emotion of recent days but some 250 miles (400km) away in Harwich, Essex, landlord Nick May agreed with Sue. His first instinct had been to close his pub, The Alma, out of respect, but his staff persuaded him to stay open.

“This is a group moment of grief,” Nick said. Gathered in the bar were about 35 people from around the coastal town. Several were veterans. Others, said Nick, had lost parents or grandparents and saw the Queen as a reminder of times past.

Waiting for the service to begin, Andrew Smith stood in Birmingham’s Centenary Square and felt goosebumps rising on his arm. He and his wife Margaret, from Barnwell, Northamptonshire, were in the city to celebrate their 51st wedding anniversary.

Margaret’s mind was on 1953, when she had been taken to watch the Queen’s coronation at her nan’s house and later to a street party. “She’s like our grandmother, she’s always been there,” Margaret said, visibly emotional.

At 11:00, the funeral was under way. The Very Rev David Hoyle, Dean of Westminster, spoke of the Queen’s “unswerving commitment to a high calling over so many years as Queen and Head of the Commonwealth”.

Meanwhile, in Manchester’s Cathedral Gardens, rain was falling. Rebecca Watson, 38, thought of those who had filed through the streets of London over the weekend to witness the Queen’s lying-in-state and resolved to stay where she was. “If people have been in a queue for 14 hours I think we can cope with this,” she said.

As she watched in a park in Hastings, Jo Musson, 62, who had set off on holiday from her home in Worcestershire in her campervan before the Queen’s death, worried that she had not packed any black clothes.

Inside Westminster Abbey, the congregation began to sing The Lord Is My Shepherd. More than 300 miles away in Belfast, Simon Freedman, 51, from Coleraine, County Londonderry, thought of his mother, Olive. It had been her favourite hymn, but when she died of Covid in 2020 at the age of 79, the family had been unable to hold a service in which they could sing it. “I knew when that hymn came on I’d shed a tear.”

Ahead of the two minutes’ silence, everyone in the Royal British Legion, in Oldmeldrum, Aberdeenshire, stood, bowed their heads, and sang along to the national anthem.

Afterwards, a lone bagpiper played a lament. For Emma Parsons-Reid, 55, watching at home in Ely, Cardiff, with family and neighbours, it was at this point that the Queen’s death struck home. “For the first time, it felt real,” she said.

On The Mall, many spectators had watched the service on their phones. As the Queen’s coffin made its way towards them, spectators stood on tiptoes, with children lifted on to shoulders, as the crowd collectively craned its necks for a final glimpse.

Then, as the procession passed, they fell silent.

In Windsor, a committal service would be held at St George’s Chapel – where the Duke and Duchess of Sussex, Prince Harry and Meghan, were married in 2018 and where the Queen’s late husband Prince Philip’s funeral was also held.

Dianne Turner, 62, didn’t intend to go to Windsor’s Long Walk to watch the funeral procession. She had wanted to be in the crowds in central London when she had set off from Somerset but there were problems with the trains so she went to Windsor instead.

As she watched the committal service on the screens at Windsor, she wept. “I think I got so emotional because my mum loved the Queen and this would have meant a lot to her.” Dianne had never met the Queen, but – like so many others – felt as though she had.

By the time the state hearse slowly passed Dianne, taking Queen Elizabeth II towards her final resting place, businesses had already begun to reopen. Life was returning to normality.

But not entirely as before. People had paused and thought about what was gone.

Reporting by Oli Constable, Simon Hare, Gavin Bevis, Marie Jackson, Duncan Leatherdale, Maisie Olah, Margaret Ryan, Rozina Sini, Peter Walker and Laurence Cawley.