A massive cache of leaked data reveals the inner workings of a stalkerware operation that is spying on hundreds of thousands of people around the world, including Americans.

The leaked data includes call logs, text messages, granular location data and other personal device data of unsuspecting victims whose Android phones and tablets were compromised by a fleet of near-identical stalkerware apps, including TheTruthSpy, Copy9, MxSpy and others.

These Android apps are planted by someone with physical access to a person’s device and are designed to stay hidden on their home screens but will continuously and silently upload the phone’s contents without the owner’s knowledge.

SPYWARE LOOKUP TOOL

You can check to see if your Android phone or tablet was compromised here.

Months after we published our investigation uncovering the stalkerware operation, a source provided TechCrunch with tens of gigabytes of data dumped from the stakerware’s servers. The cache contains the stalkerware operation’s core database, which includes detailed records on every Android device that was compromised by any of the stalkerware apps in TheTruthSpy’s network since early 2019 (though some records date earlier) and what device data was stolen.

Given that victims had no idea that their device data was stolen, TechCrunch extracted every unique device identifier from the leaked database and built a lookup tool to allow anyone to check if their device was compromised by any of the stalkerware apps up to April 2022, which is when the data was dumped.

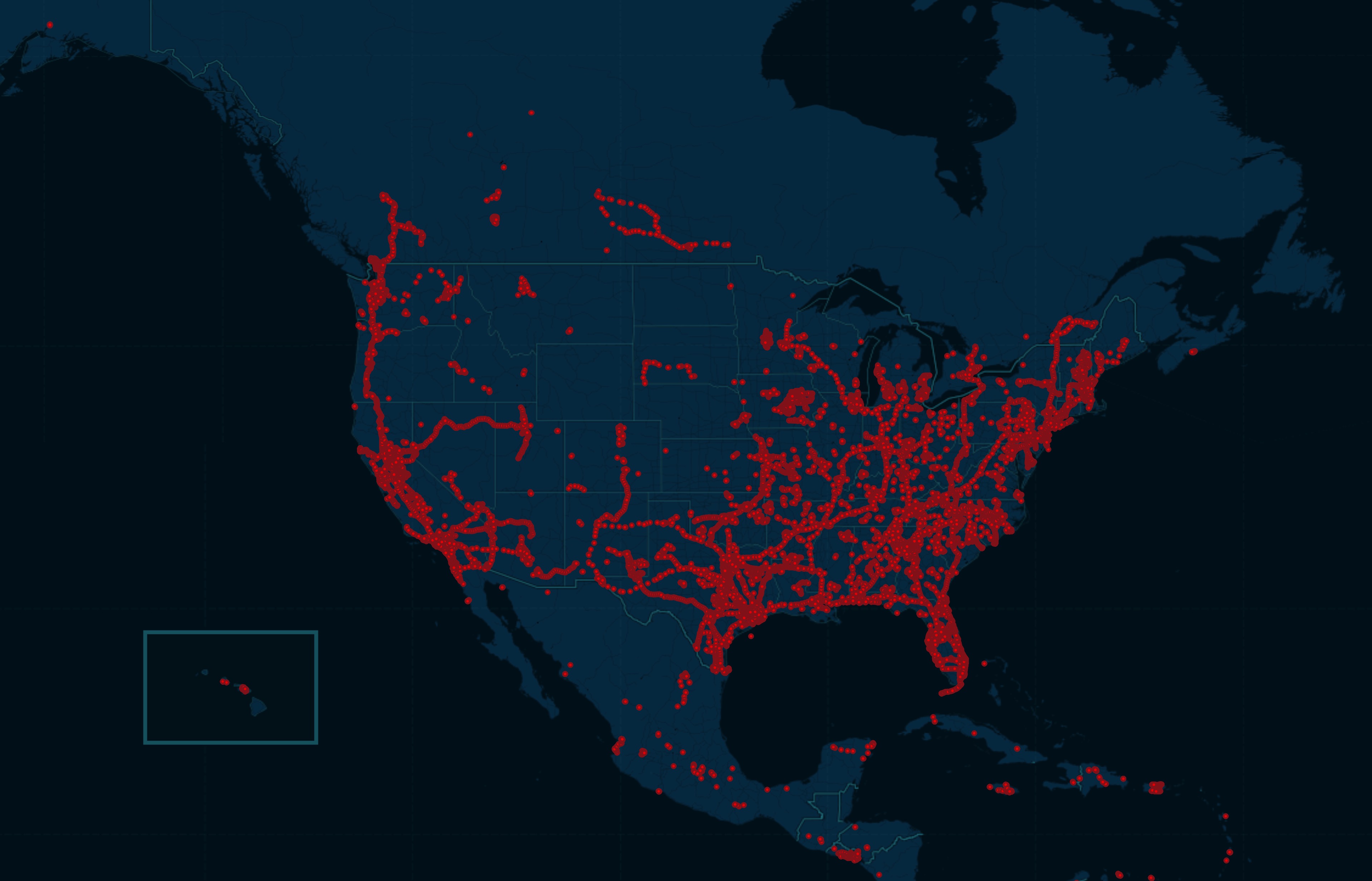

TechCrunch has since analyzed the rest of the database. Using mapping software for geospatial analysis, we plotted hundreds of thousands of location data points from the database to understand its scale. Our analysis shows TheTruthSpy’s network is enormous, with victims on every continent and in almost every country. But stalkerware like TheTruthSpy operates in a legal gray area that makes it difficult for authorities around the world to combat, despite the growing threat it poses to victims.

First, a word about the data. The database is about 34 gigabytes in size and consists of metadata, such as times and dates, as well as text-based content, like call logs, text messages and location data — even names of Wi-Fi networks that a device connected to and what was copied and pasted from the phone’s clipboard, including passwords and two-factor authentication codes. The database did not contain media, images, videos or call recordings taken from victims’ devices, but instead logged information about each file, such as when a photo or video was taken, and when calls were recorded and for how long, allowing us to determine how much content was exfiltrated from victims’ devices and when. Each compromised device uploaded a varying amount of data depending on how long their devices were compromised and available network coverage.

TechCrunch examined the data spanning March 4 to April 14, 2022, or six weeks of the most recent data stored in the database at the time it was leaked. It’s possible that TheTruthSpy’s servers only retain some data, such as call logs and location data, for a few weeks, but other content, like photos and text messages, for longer.

This is what we found.

This map shows six weeks of cumulative location data plotted on a map of North America. The location data is extremely granular and shows victims in major cities, urban hubs and traveling on major transport lines. Image Credits: TechCrunch

The database has about 360,000 unique device identifiers, including IMEI numbers for phones and advertising IDs for tablets. This number represents how many devices were compromised by the operation to date and about how many people are affected. The database also contains the email addresses of every person who signed up to use one of the many TheTruthSpy and clone stalkerware apps with the intention of planting them on a victim’s device, or about 337,000 users. That’s because some devices may have been compromised more than once (or by another app in the stalkerware network), and some users have more than one compromised device.

About 9,400 new devices were compromised during the six-week span, our analysis shows, amounting to hundreds of new devices each day.

The database stored 608,966 location data points during that same six-week period. We plotted the data and created a time lapse to show the cumulative spread of known compromised devices around the world. We did this to understand how wide-scale TheTruthSpy’s operation is. The animation is zoomed out to the world level to protect individuals’ privacy, but the data is extremely granular and shows victims at transportation hubs, places of worship and other sensitive locations.

By breakdown, the United States ranked first with the most location data points (278,861) of any other country during the six-week span. India had the second most location data points (77,425), Indonesia third (42,701), Argentina fourth (19,015) and the United Kingdom (12,801) fifth.

Canada, Nepal, Israel, Ghana and Tanzania were also included in the top 10 countries by volume of location data.

This map shows the total number of locations ranked by country. The U.S. had the most location data points at 278,861 over the six-week span, followed by India, Indonesia, and Argentina, which makes sense given their huge geographic areas and populations. Image Credits: TechCrunch

The database contained a total of 1.2 million text messages, including the recipient’s contact name, and 4.42 million call logs during the six-week span, including detailed records of who called whom, for how long, and their contact’s name and phone number.

TechCrunch has seen evidence that data was likely collected from the phones of children.

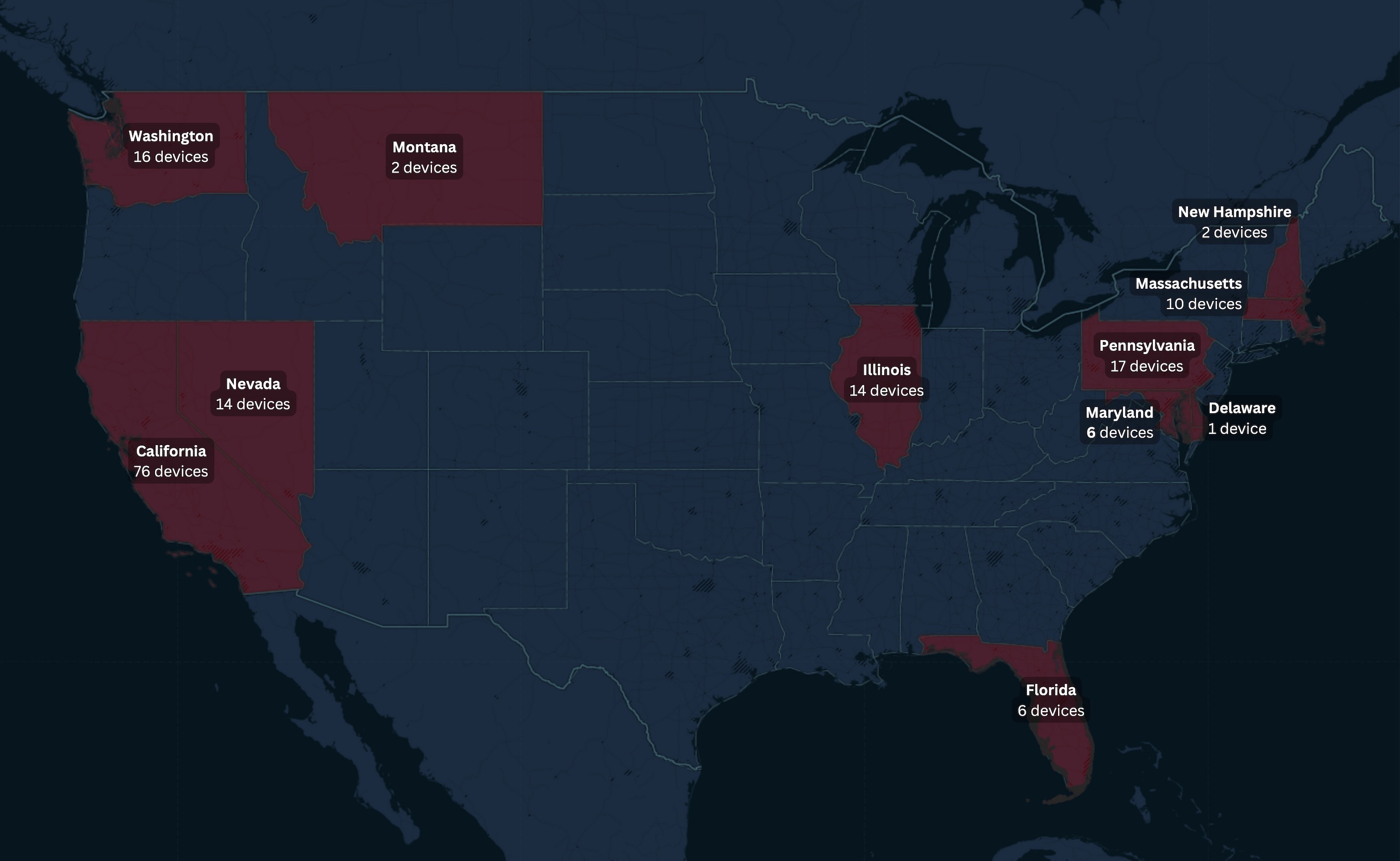

These stalkerware apps also recorded the contents of thousands of calls during the six weeks, the data shows. The database contains 179,055 entries of call recording files that are stored on another TheTruthSpy server. Our analysis correlated records with the dates and times of call recordings with location data stored elsewhere in the database to determine where the calls were recorded. We focused on U.S. states that have stricter phone call recording laws, which require that more than one person (or every person) on the line agree that the call can be recorded or fall foul of state wiretapping laws. Most U.S. states have statutes that require at least one person consents to the recording, but stalkerware by nature is designed to work without the victim’s knowledge at all.

We found evidence that 164 compromised devices in 11 states recorded thousands of calls over the six-week span without the knowledge of device owners. Most of the devices were located in densely populated states like California and Illinois.

TechCrunch identified 164 unique devices that were recording the victim’s phone calls during the six-week period and were located in states where telephone recording laws are some of the strictest in the United States. California led with 76 devices, followed by Pennsylvania with 17 devices, Washington with 16 devices and Illinois with 14 devices. Image Credits: TechCrunch

The database also contained 473,211 records of photos and videos uploaded from compromised phones during the six weeks, including screenshots, photos received from messaging apps and saved to the camera roll, and filenames, which can reveal information about the file. The database also contained 454,641 records of data siphoned from the user’s keyboard, known as a keylogger, which included sensitive credentials and codes pasted from password managers and other apps. It also includes 231,550 records of networks that each device connected to, such as the Wi-Fi network names of hotels, workplaces, apartments, airports and other guessable locations.

TheTruthSpy’s operation is the latest in a long line of stalkerware apps to expose victims’ data because of security flaws that subsequently lead to a breach.

While the possession of stalkerware apps is not illegal, using it to record calls and private conversations of people without their consent is illegal under federal wiretapping laws and many state laws. But while it is illegal to sell phone monitoring apps for the sole reason of recording private messages, many stalkerware apps are sold under the guise of child monitoring software, yet are often abused to spy on the phones of unwitting spouses and domestic partners.

Much of the effort against stalkerware is led by cybersecurity companies and antivirus vendors working to block unwanted malware from users’ devices. The Coalition Against Stalkerware, which launched in 2019, shares resources and samples of known stalkerware so information about new and emerging threats can be shared with other cybersecurity companies and automatically blocked at the device-level. The coalition’s website has more on what tech companies can do to detect and block stalkerware.

But only a handful of stalkerware operators, such as Retina X and SpyFone, have faced penalties from federal regulators like the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) for enabling wide-scale surveillance, which has relied on using novel legal approaches to bring charges citing poor cybersecurity practices and data breaches that fall more closely within their regulatory purview.

When reached for comment by TechCrunch ahead of publication, a spokesperson for the FTC said the agency does not comment on whether it is investigating a particular matter.

If you or someone you know needs help, the National Domestic Violence Hotline (1-800-799-7233) provides 24/7 free, confidential support to victims of domestic abuse and violence. If you are in an emergency situation, call 911. The Coalition Against Stalkerware also has resources if you think your phone has been compromised by spyware. You can contact this reporter on Signal and WhatsApp at +1 646-755-8849 or zack.whittaker@techcrunch.com by email.

Inside TheTruthSpy, the stalkerware network spying on thousands by Zack Whittaker originally published on TechCrunch

DUOS