When Susan Wamaitha started feeling sick a year ago, she thought it was the side effects of a contraceptive pill she had started taking a few months earlier – but it turned out that she was eight weeks pregnant.

The 32 year old is now a mother of three children. Unbeknown to her, the pill that she began using in June 2021 was banned in Kenya.

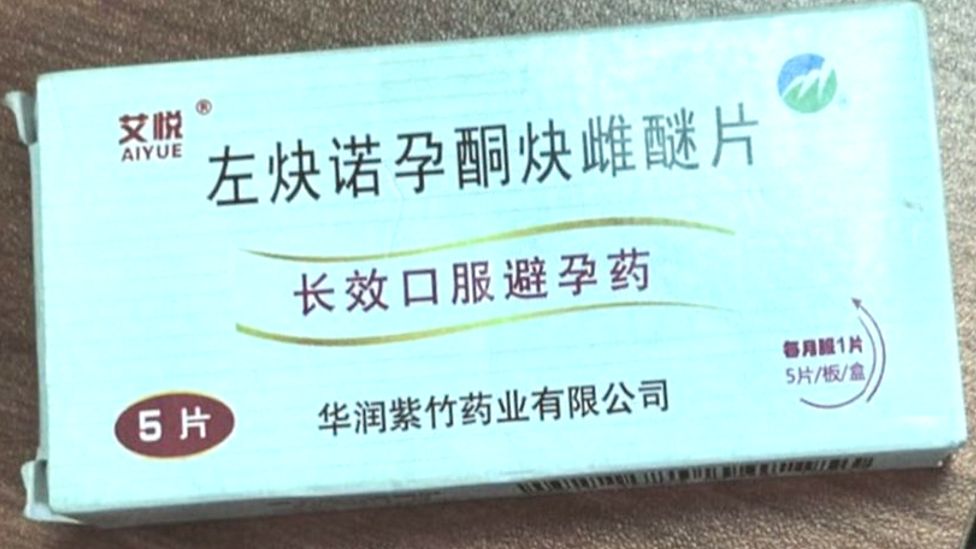

Its street name in Kenya is “Sofia” but it is manufactured in China and all the details about the product on the packaging are only written in Chinese.

A translation of the first line says it contains “Levonorgestrel Fast Estradiol Tablets”. The pill is a “long-acting oral contraceptive”, according to the second line. Then there is information about the manufacturer on the third: “Zizhu Pharmaceutical Co Ltd”.

The sale of the pill was prohibited by Kenya’s authorities 10 years ago because of high levels of levonorgestrel – more than 40 times the recommended levels.

Levonorgestrel is a hormonal medication used in a number of birth control methods.

The health ministry did not share the full lab results about its findings, but said children conceived after the pill failed were found to have developed early puberty.

Headaches and nausea

“I did not know it was banned. Many of my friends were using it and had no side effects,” Ms Wamaitha told the BBC.

Like many other Kenyan women, she was attracted to the pill by its affordability and the convenience of taking it only once a month.

Women tend to buy the Sofia tablet each month – most suppliers will not sell it in bulk. Each pill costs between 300 Kenyan shillings ($2.50; £2.20) and 400 Kenyan shillings.

Other family planning methods available in the country include the daily contraceptive pill. A month’s supply costs about $1.70 from government hospitals but their stock is not always guaranteed so women then have to buy it from pharmacies for considerably more.

This makes the hormonal implant that lasts three months, offered at state clinics at a cost of around $5, and various intrauterine devices, like coils, that last several years and cost up to $9, more common alternatives.

Condoms are offered for free in public offices and toilets but sometimes run out, though they can be bought in shops.

“Because I had a non-hormonal copper T-shaped coil that was giving me back pains, I decided to remove it and use the pill,” Ms Wamaitha told the BBC.

She was also impressed that her friends who recommended Sofia had not gained any weight – a key consideration for her as she says she struggles with keeping the pounds off.

However, right from the beginning she did not feel great on it – though she thought it would just take time for her body to get used to the new medication as she had to take two pills initially followed by one a month.

“I started having headaches and nausea. The first month I missed my period,” Ms Wamaitha said.

But she did not worry as she had her period the following month. It was only when it skipped again in the third month that she began to get concerned.

Her husband then started researching the contraceptive pill and that is when he found out it had been banned.

“We started panicking about using a banned pill and when I realised I was pregnant I was worried about the effects it may have on my baby,” she said.

They now have a healthy three-month-old girl, but the couple are upset by the lack of information and possible implications for their daughter as she grows up.

‘One size does not fit all’

Only 50% of women in sub-Saharan Africa in need of modern contraceptive methods have access to them, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

In Kenya, contraception tends to be discussed in hushed tones – mostly because of cultural and religious beliefs in what is a patriarchal society.

Some men do not allow their wives to use contraceptives while some religious sects are against it. The Kavonokya Sect in eastern Kenya, for example, rejects all modern medicine as it believes the Bible only recommends prayer as an intervention.

For population and development expert Dr Josephine Kibaru, a grassroots approach would be best to gain acceptance for modern family planning methods.

“We need community health volunteers to be more empowered with information because a woman is likely to trust a neighbour and friend more than a healthcare worker who has been posted at the dispensary,” Dr Kibaru told the BBC.

She says there is a chasm of ignorance about the birth control methods available, along with many myths and misconceptions that need to be dispelled.

A combination of both is probably what is required as gynaecologist Brigid Monda says women should consult healthcare providers to be able to find a family planning method that works for them.

“One size does not fit all,” she told the BBC.

Yet some women have also been forced to mix different contraceptive methods because of a lack of consistent supply at dispensaries located in rural areas.

Sofia remains easily available despite its ban. The fact that women do not know it is banned is down to poor public health messaging, according to Dr Kibaru.

“Using the media alone is not enough. Intentional public messaging at grassroots level is important to ensure the masses understand well why a drug has been banned,” she says.

Sold to trusted customers

Pharmacists do know it is banned – another warning was issued by the health ministry last month – yet they still sell the pill because of demand.

It is not on display, but sold under the counter to trusted customers who come in to buy it each month.

The BBC visited several pharmacies in the capital, Nairobi, to make inquiries about Sofia – most said the drug was not for sale.

One seller – who spoke on condition of anonymity – explained that it was available, just not on display, and pharmacies were able to buy it from suppliers who brought it in from neighbouring countries.

Earlier this month, a Pharmacy and Poisons Board (PPB) official told Kenya’s Standard newspaper a shipment had been intercepted at the Ugandan border.

Ms Wamaitha says she actually bought her pills from a friend who gets them in bulk from one of these suppliers.

She says this friend and others knew the pill was banned when they recommended it to her.

Her pregnancy has not persuaded them to stop using it – nor do any of the complaints on the various Facebook groups for Kenyan mothers.

On at least three of these forums there have been discussions about Sofia, where several women taking it said they had fallen pregnant.

This has convinced Ms Wamaitha to keep on urging her friends and other women to consider a different form of birth control.

“I just know that the mention of that Sofia pill makes me get chills on my body. I don’t know what family planning method I will use to prevent a fourth pregnancy, but I’m done, done with that pill.”