A group of African Americans has filed a lawsuit to stop the return of some Benin Bronzes from the Smithsonian Museum in Washington DC to Nigeria.

They claim that the bronzes – looted by British colonialists in the 19th Century from the kingdom of Benin in what is now Nigeria – are also part of the heritage of descendants of slaves in America, and that returning them would deny them the opportunity to experience their culture and history.

“It is a very interesting argument,” says 93-year-old David Edebiri, after laughing for about 15 seconds straight.

He is part of the cabinet of the current Oba of Benin – the king or traditional ruler in southern Nigeria’s Edo state.

“But the artefacts are not for the Oba alone. They are for all Benin people, whether you are in Benin or in the diaspora.”

Most Nigerians with whom I have discussed this US lawsuit have burst into laughter.

But Deadria Farmer-Paellmann, the founder and executive director of the Restitution Study Group (RSG) which initiated it, is dead serious.

The 56-year-old founded RSG, a not-for-profit institute based in New York, in 2000 “to examine and execute innovative approaches to healing the injuries of exploited and oppressed people”.

More than 103,000 slaves brought to the America were from ports once controlled by traders from the kingdom of Benin, such as Lagos, says Ms Farmer-Paellmann.

She is quoting records from the Transatlantic Slave Trade Database hosted by Emory University in Atlanta – and recent testing showed that 27.7% of her DNA is linked to these people.

This, she believes, gives her and the millions of others with similar ancestry the right to lay a claim to the bronzes.

Her argument hinges on manillas, brass bracelets introduced as a form of currency by Portuguese traders, who from the 16th to the 19th Centuries purchased from Africans a variety of agricultural produce and local goods – and also human beings.

The thousands of sculptures known collectively as the Benin Bronzes that were looted after the infamous punitive attack on the palace of Oba Ovonramwen Nogbaisi in 1897 were made with a combination of metals, such as brass and copper.

The kingdom itself did not produce enough metal to supply its casting industry, and relied on imports – including the brass metal from these bracelets, which were melted down to create works of art.

“Fifty manillas would buy a woman, 57 would buy a male slave,” says Ms Farmer-Paellmann.

“What we are saying is that the descendants of the people traded for these manillas have a right to see the bronzes where they live,” she says

“There is no reason why we should be obligated to travel to Nigeria to see them,” she said, citing US travel warnings. “I don’t want to get kidnapped.”

‘Afro-pessimism’

Critics of the case, like Mr Edebiri, argue that not all manillas used in Benin were from the slave trade.

He has written a book about his great-great-grandfather Iyase Ohenmwen, who was prime minister for the Oba in the early 19th Century, detailing how he traded in ivory and European clothes.

“He would take these manillas to Igun-Eronmwon, a village in Benin that manufactured all these artefacts. They would then make them into the bronzes and other fanciful things.”

Acclaimed Nigerian-American artist Victor Ehikhamenor, who is from Edo state, argues that while history is complicated, one matter is simple: “The exact land from where these things were taken has not shifted.”

For Nigerian art historian Chika Okeke-Agulu, a professor at Princeton University and an activist at the forefront of the campaign to return looted artwork, Ms Farmer-Paellmann’s comments “sound like the arguments that white folks who don’t want to return the artefacts have made”.

“The lack of safety strikes me as another version of Afro-pessimism that we’ve heard for a long time,” he says, pointing to the thousands of African Americans who now travel to south-western Nigeria every year for the famous Yoruba Osun Osogbo festival.

Agitation for the return of the bronzes to Nigeria has been ongoing since the 1930s.

“Being in the British Museum, which is a world repository of heritage, allows people to see it,” said Oliver Dowden, a former British culture minister, last year.

But since then some institutions in the West have finally started to return them.

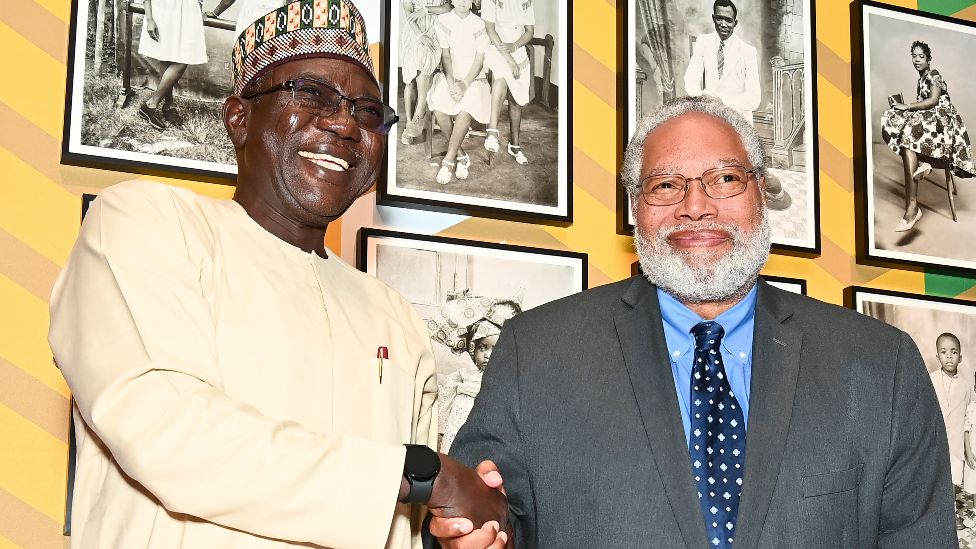

The Smithsonian Museum of African Art, in a ceremony on 11 October, transferred ownership of 20 of them to Nigeria, while nine more will remain on loan to the museum.

Another 20 are with the Smithsonian’s Museum of National History, and the process that could lead to their transfer has begun. The Restitution Study Group’s lawsuit hopes to stop that.

‘We are suffering from shame’

Ms Farmer-Paellmann has long been fighting for justice and reparations for the black descendants of slaves in the US.

In the 1990s, she started compiling evidence to show how 17 companies had amassed wealth from slavery, such as the insurance firm Lloyd’s of London. The legal proceedings floundered in the end in the 2000s as RSG ran out of funding.

However, following the global Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, Lloyd’s of London apologised for its past links to the slave trade and committed to making financial investments to promote the welfare of black, Asian and ethnic minority groups.

Each time I have written about the legacy of slavery in Africa, I have received hundreds of messages from African Americans expressing worry that my stories might affect their quest for reparations from white descendants of slave owners, who might use stark evidence of African involvement in the transatlantic slave trade as an excuse to wriggle out of blame for their ancestors’ atrocities.

Therefore, I was surprised that a group like Ms Farmer-Paellmann’s would be openly highlighting this fact through its lawsuit.

“There’s a lot of shame,” she admits. “It’s almost like a child reporting their mother for child abuse. That’s a hard thing to do.”

“But we are suffering from the shame while the slave trader heirs are walking off with the treasures.”

She calls for a more understanding outlook: “This is an opportunity for Nigeria to take a stand, one of the biggest places where descendants of enslaved people come from – about 3.6 million of us – and say that the honourable thing to do today is to share these bronzes.

“Nigeria would be celebrated for doing something like that.”