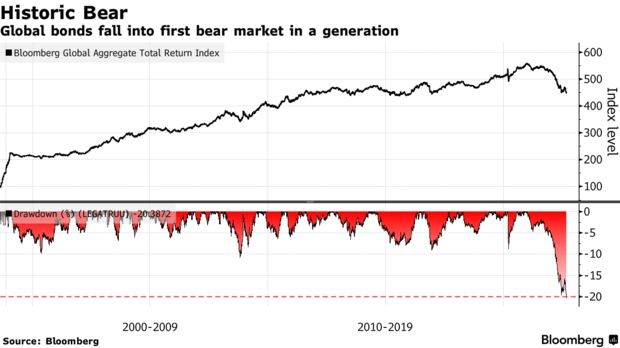

Under pressure from central bankers determined to quash inflation even at the cost of a recession, global bonds slumped into their first bear market in a generation.

The Bloomberg Global Aggregate Total Return Index of government and investment-grade corporate bonds has fallen more than 20% from its 2021 peak, the biggest drawdown since its inception in 1990. Officials from the US to Europe have hammered home the importance of tighter monetary policy in recent days, building on the hawkish message from Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell at the Jackson Hole symposium.

Rapid interest-rate hikes deployed by policy makers in response to soaring inflation have brought to an end a four-decade bull market in bonds. That’s creating a difficult environment for investors, with bonds and stocks sinking in tandem.

“I suspect that the secular bull market in bonds that started in the mid-1980s is ending,” said Stephen Miller, who’s covered fixed income since then and now works as an investment consultant at GSFM, a unit of Canada’s CI Financial Corp. “Yields aren’t going to return to the historic lows seen both before and during the pandemic.”

The elevated inflation the world now faces means central banks won’t be prepared to re-introduce the sort of extreme stimulus that helped send Treasury yields below 1%, he said.

The simultaneous swoons for fixed-income and equity assets are undermining a mainstay of investing strategies over the past 40 years or more. Bloomberg’s bond gauge is down 16% in 2022, while MSCI Inc.’s index of global stocks has slumped 19%.

That has pushed a US measure of the classic 60/40 portfolio — where investments are split by those proportions between stocks and bonds — down 15% this year, on track for the worst annual performance since 2008.

‘Huge Deal’

“We are in a new investment environment, and this is a huge deal for those expecting fixed income to be a diversifier to risk off in equities,” said Kellie Wood, a fixed-income money manager at Schroders Plc in Sydney.

European bonds have been hit hardest this year as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sends natural gas prices soaring. Asian markets have suffered less, aided by China’s debt, as the central bank there eases policy to try and turn around the world’s second-largest economy. Investment-grade dollar bond spreads narrowed last month by the most since 2020, driving them tighter than those of US peers, something that’s happened only a few times in the last decade.

The switch in much of the world from unprecedented easing to the steepest rate hikes since the 1980s has dried up liquidity, according to JPMorgan Chase & Co.

“Bond and currency markets have seen more severe and more persistent deterioration in liquidity conditions this year relative to other asset classes with little signs of reversal,” strategists including Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou in London wrote in a research note. Bearish bond momentum is approaching extreme levels, they said.

Back to ’60s

In many ways, the economic and policy realities now facing investors hark back to the 1960s bear market for bonds, which began in the second half of that decade when a period of low inflation and unemployment came to a sudden end. As inflation accelerated through the 1970s, benchmark Treasury yields surged. They would later hit almost 16% in 1981 after then Fed Chair Paul Volcker had raised rates to 20% to tame price pressures.

Powell cited the 1980s to back his hawkish stance at Jackson Hole, saying “the historical record cautions strongly against prematurely loosening policy.” Swaps traders now see almost 70% odds that the Fed will deliver a third straight 75 basis-point hike when it meets later this month.

Other central bankers at Jackson Hole, from Europe to South Korea and New Zealand, also indicated that rates will continue to rise.

Still, fixed-income investors are showing plenty of demand for government bonds as yields rise, aided by lingering expectations that policy makers will need to reverse course should economic slowdowns help cool inflation. In the US, options markets are still pricing in at least one 25 basis-point rate cut next year.

“I wouldn’t characterize the current trend as a new secular bond bear market but more of a necessary correction from a period of unsustainably ultra-low yields,” said Steven Oh, global head of credit and fixed income at PineBridge Investments LP. “Our expectations are that yields will remain low by long-term historical standards and 2022 is likely to represent the peak in 10-year bond yields in the current cycle.”

Schroders is also starting to see some value in government bonds as yields rise and it positions portfolios for the real risk of severe economic slowdowns, according to Wood.

“In the not so distant future, there is going to be a cracking opportunity to be buying bonds as central banks guarantee us a global recession,” she said.