The leadup to Ghana’s budget presentation was filled with political drama and outsized investor expectations.

On Thursday, the 24th of November, the much anticipated event finally came off, in the shadow of a World Cup fixture between Ghana and Portugal.

The budget, as finally presented, has many twists and turns but on the essentials it is a bit of a Frankenstein mash-up.

On the one hand, it contains the clearest yet admission by the government that the fiscal situation is dire, in ways that are not predominantly attributable to external factors like the Ukraine conflict and the COVID-19 pandemic, and therefore that significant waste-cutting is warranted.

It is a standard practice of Ghanaian budget speech-drafting during economic downturns to frame the domestic crisis against the global picture. Below are extracts from the 1999 and 2000 budgets, when the Asian Financial Crisis was looming large.

The 2023 budget had its fair share of global scapegoating but not to an extent where all emphasis on domestic triggers of the crisis was totally neglected as has been the case in most policy statements of recent times.

Yet, on the other hand, the bulk of the numbers do not add up anywhere close to the much speculated austerity package. In fact, this is one of the most expansionary budgets in the history of Ghana, at a time most investors and analysts expected contractionary policy.

The government’s approach harks back to the failed fiscal consolidation approach in 1999.

Total Ghana government expenditure in 1998 was 4.38 trillion Cedis or $1.64 billion against nominal GDP of 16.59 trillion Cedis (or $6.3 billion at the then prevailing exchange rate) yielding an expenditure-to-GDP ratio of ~25%. Faced with domestic and external headwinds, the economic managers of the time decided instead to increase spending to 28% of GDP as evidenced in the extracts below from the 2000 budget statement.

As everyone now knows the 1999-2000 fiscal consolidation effort, not surprisingly, failed completely and the succeeding government was forced to declare HIPC for concessional terms in the restructuring of Ghana’s debt.

A far better lesson for today’s economic managers should come from the crisis budget design of 1995, the Kumepreko year. Against the 1994 outturn, government reversed back to back deficits and generated a fiscal surplus by spending 1.15 trillion Cedis/$800 million (from revenues of 1.26 trillion Cedis/$870 million) to result in an expenditure-to-GDP ratio of 16% (i.e. using a GDP figure of $5 billion at the prevailing exchange rate).

Against this historical background, one marvels at the government’s decision to project expenditure to GDP at more than 28% in 2023 (from ~25% in 2021) in the hopes of almost doubling revenue (from a likely outturn of 85 billion GHS in 2022 to an expected 143 billion GHS in 2023).

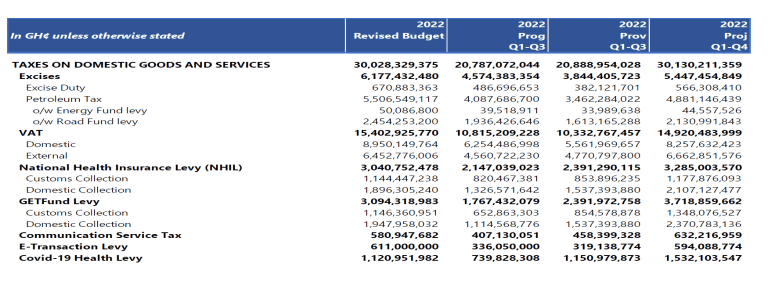

To seek to grow government revenue by more than 68% in one year at a time of collapsing demand, imploding confidence and low economic growth is clearly wishful thinking. That way of thinking is reminiscent of the government’s insistence on raising billions from its highly unpopular e-Levy despite widespread analyst sentiment against such projections. In the event, e-Levy could not even clock 6% of the original target by end of September 2022.

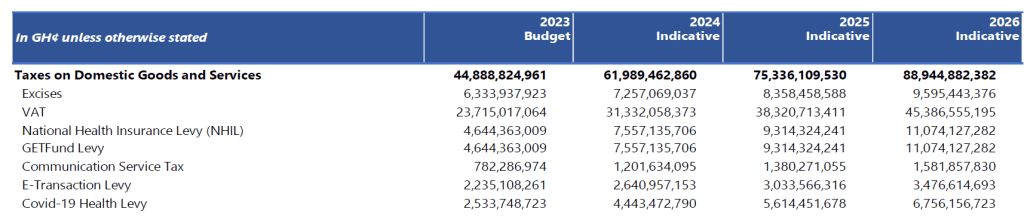

There is no evidence of government learning any lessons from this episode. Massive increases are projected in 2023 for VAT (an expected 65% increase in 2023 over the 2022 outturn), e-Levy (a near 500% increase on the likely 2022 outturn) and COVID-19 Health Levy (an expected doubling of the yield seen in 2022).

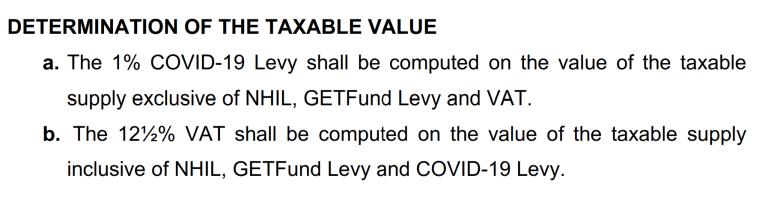

It is impossible to fathom why the government expects the COVID-19 levy (initially sold to the country as a temporary revenue measure) to grow at more than twice the rate of NHIL when the base for computing both taxes are the same. In fact, all these levies, under normal circumstances, should grow proportionately as VAT increases.

Such a lack of credible revenue estimation in a critical budget such as this, one which investors and analysts all over the world have been awaiting to use as a gauge of fiscal direction, is most worrying.

Equally bizarre is the decision to project an increase in expenditure from an estimated 137 billion GHS (cash basis) in 2022 to an estimated 227 billion GHS (a 66% increase).

It is evident from this budget design that the government is not keen on contractionary policy at this time. Despite repeated demands from civil society and policy think tanks for it to commission a root and stem independent spending review to assist in jettisoning obligations of dubious value contracted by various government assigns and state-owned enterprises to benefit business cronies, the budget is instead replete with symbolic moves like banning the use of SUVs by Ministers for municipal commuting.

Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) and policy think tanks such as IMANI and ACEP have for many years and months now documented massive leakages in the energy sector and elsewhere amounting to billions of dollars. Yet, unconscionable public sector contracts like the Kelni GVG deal continue to subsist.

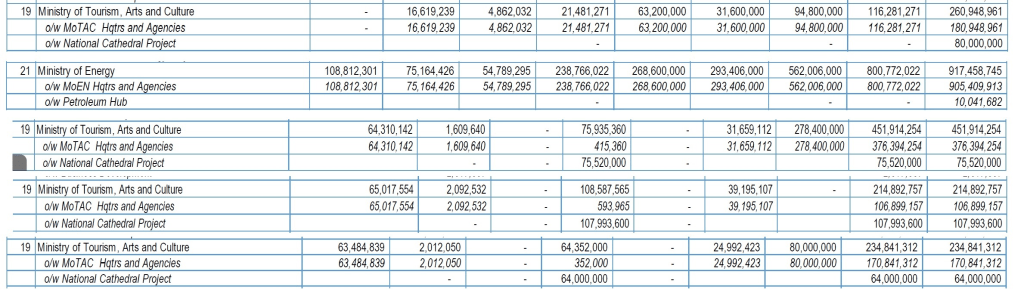

Even more alarmingly, the budget itself contains spending proposals that persist in the tradition of prioritising non-essential spending even in a time of serious crisis. Why should a government confronted with such dire fiscal numbers authorise the medium-term spending of ~330 million GHS on a “national cathedral” or for continued consultancy spending on a so-called Petroleum Hub that has failed to attract any significant investor interest?

The price for sustaining the continued spending on non-essentials is the dangerous resort to pro-cyclical measures such as the increase in the broadest-based consumption tax (VAT) by a whopping 2.5% percentage points. One shouldn’t be an uncritical devotee of Arthur Laffer to protest strongly against broad-based tax rises in a time of fast falling confidence in the economy and steadily collapsing demand.

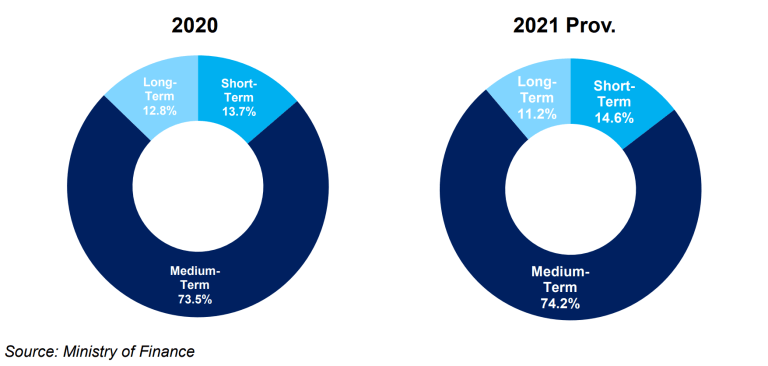

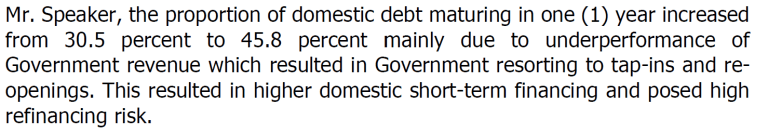

This, in a country where the loss of investor confidence has reversed earlier debt management gains from the lengthening of maturity profiles back to the dark days of overreliance on short-term debt.

At the end of 2021, short-term securities constituted just 14.6% of total domestic debt. Today, the figure has climbed steadily to nearly 50%.

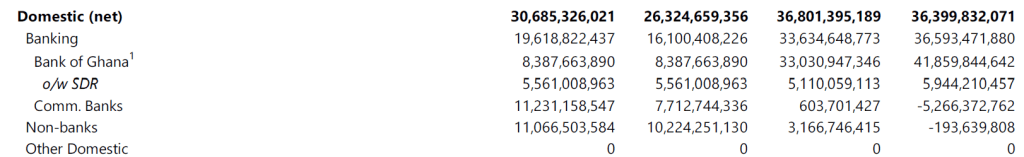

The shift to expensive short-term borrowing is reinforced by a growing reliance on the Central Bank for deficit financing.

The Central Bank’s accommodative stance towards fiscal expansion is now complete. In addition to sweetheart repo deals in the commercial banking sector to prop up artificial demand for government of Ghana domestic debt issuances, the Bank of Ghana has also allowed overdraft financing of the central government to violate every public financial management norm in existence.

Both trends – aggressive central bank financing of the deficit and a shift to expensive short-term debt securities – result from a complete inability to deliver on the promised fiscal contraction. 2022 expenditure has already hit 159 billion GHS on commitment basis despite claims of cutting “discretionary spending” by 30%. The nominal increase on 2021 spending levels of 113 billion GHS is 39%, or 29% in real terms. In simple terms, despite bold promises of a significant reduction in spending (including repeated assertions of a “30% cut in discretionary spending”), fiscal expansion has been galloping at an uncontrollable pace. Meanwhile, the inflationary and exchange rate depreciation spiral is set to continue, deepening the downturn cycle.

The government’s decision to continue budgeting hundreds of millions of GHS for non-essential spending like the cathedral and to support non-strategic defense spending, like the inexplicable decision to keep supporting the construction of some forward-operating bases, such as the one to protect the Bui Dam (well beyond the country’s well-acknowledged need for a shield against spillovers from the deteriorating Sahelian security environment), among others, is ample evidence of a lack of commitment to true crisis budgeting.

Whilst we continue to analyse the 2023 budget for deeper insights into the government’s fiscal prospects in 2023 and the quality of the planned IMF ECF program, our initial assessment is not encouraging. Once again, the lack of meaningful prior consultation, even within the ruling party, has resulted in an underwhelming document unlikely to restore serious confidence in the economy.