The State of Ghana’s Economic Crisis

Ghana’s inflation and exchange rate crisis is deepening and fears are mounting of a newer, more devastating, phase: a full run on the local currency, the Cedi (GHS), which has year-to-date lost more than 50% of its value on the retail end of the market.

The government’s problem diagnosis and corresponding policy responses so far can be summarized as follows:

- For slow growth and inflation, blame external factors – COVID-19 and the Russia-Ukraine conflict in particular – for the entire problem, and admit no flaws in policy.

- For exchange rate depreciation, blame speculators aided by criminal black market operators, and admit no flaws in policy.

- Nonetheless, raise the policy (interest) rate in order to abate inflationary pressures,

- Continue to predict near-term improvement based on an imminent IMF deal and the arrival of certain official foreign loans.

- Catch and jail more tax evaders.

Some of these policies are understandable but taken as a whole they mostly miss the mark.

The True Driver of Inflation

Ghana’s Central Bank has said repeatedly that domestic inflation is currently “generalized” and is not driven primarily by imported inflation. Raising domestic interest rates, as it has done multiple times in recent months to cumulatively reach a 5-year high, to tackle primarily imported inflation would be preposterous.

The key driver of inflation in Ghana is self-evident in fiscal policy. In the first 9 months of this year, the government earned 51.5 billion GHS in income. Despite pledges to cut 30% of discretionary expenditures, it ended up spending nearly 90 billion GHS. This is despite escalating arrears (that is to say refusal to pay many overdue bills). Shut out of international markets, it has resorted to borrowing 41.2 billion GHS to plug the gap (fiscal deficit) and pay interest and principal due on debt.

Because investors have cooled towards government debt, a significant portion of the gap financing has been provided by the Central Bank in various forms. Using the net growth in outstanding stock of government securities on the fixed income market (GFIM) as a gauge of market financing of the government deficit, and taking out the funds plucked from the Petroleum Stabilisation Fund (virtually wiped out now), one can deduce “monetization” in the region of 25 billion GHS. When governments have their central banks create money out of thin air to spend, inflation is always and inevitably the end result.

Blaming the Russia-Ukraine conflict would only add up if Ghana were exceptionally exposed to that region. Fortunately, on many indicators such as trade and investment, Ghana is not even among the top 20 African countries with high levels of exposure. How then is inflation in Ghana the fastest rising in Africa behind only Sudan and Zimbabwe?

Readers will also recall recent decisions by the government to impose certain taxes, particularly the e-Levy, that analysts predicted will be pro-inflationary because of their generalized impact and corrosive effect on confidence.

An update on Ghana’s economy is overdue. So here goes. This essay is a series of notes to be read leisurely. Some key takeaways:

– Speculation is NOT the reason for the Cedi’s woes.

– The govt is not laying good ground for the IMF deal.

– Govt, cut WASTE!https://t.co/dAML9CIMbC— Bright Simons (@BBSimons) October 23, 2022

In short, the government’s inability to rein in the fiscal deficit despite being shut out of the Eurobond market is the driver of Inflation.

Readers who find it difficult to accept this author’s downplaying to secondary status of the very real external contributors to the current difficulties like COVID-19, the US FED rate hikes and the Russia-Ukraine conflict etc. should take cue from the disclosures, reproduced below, made by the government to international investors during its bond issuance in early 2020 before COVID-19 was declared a pandemic.

During the first nine months of 2019, Ghana’s debt stock rose to US$39.2 billion as at 30 September 2019, of which approximately US$19.1 billion comprises domestic debt and approximately US$ 20.1 billion was external. In addition, to the extent the Government faces further challenges in the energy and financial sectors that have not been budgeted for, the Republic may need to raise additional debt to fund such unbudgeted amounts. Debt service (interest and principal repayments) as a percentage of total Government revenue reached 44 per cent. for the year ended 31 December 2018, compared to 47 per cent. in 2017, and the Government expects that debt servicing costs as a percentage of total revenues in 2019 will account for approximately 60 per cent. of total revenues, compared to a budgeted amount of 52.1 per cent.

Extract from the Government of Ghana Global Notes Prospectus (February, 2020)

The government, where it is bound to candour, openly admits that the current economic challenges have been building up well before the current global headwinds.

Speculation vs Hedging

It is very hard to have such high inflation without corresponding exchange rate depreciation because most rational economic actors in the country will seek to find ways to preserve the value of their assets.

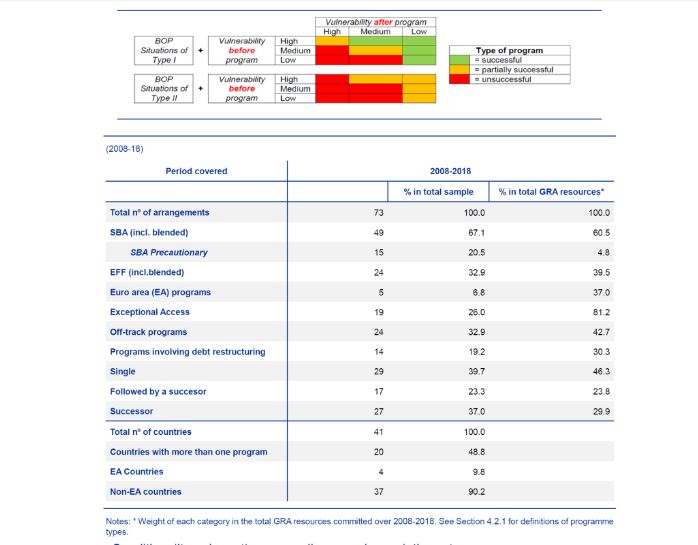

Whilst there are multiple factors involved with complex interrelationships, as in the diagram below, the linkage becomes stronger when the effects are so pronounced.

Rational economic actors with low confidence in the economy, dealing with the fast erosion of the value of their assets due to inflation, and struggling to invest because of uncertainty in the policy direction, will seek to hedge through the cheapest and most reliable instrument. In shallow markets with limited supply of various derivatives, especially forwards and futures products, the dollar or other hard currencies are the most sensible options.

Such actions must be carefully distinguished from speculation. Speculation primarily involves the use of risk capital to make gains from future shifts in the exchange rate, known in the jargon as “Inter-temporal carry-overs”. Sometimes those speculating are following the herd or trying to find the right bandwagon. But profit is a major intention. In that sense, speculators can actually be stabilizing if they sense that the local currency will rise in the future and start to dump their inventories of foreign currencies forcing the rate to align with the long-run equilibrium rate. Many theorists even go as far as argue that speculation at variance with fundamentals is always loss-making and thus unsustainable.

The government’s focus on speculators is wrongheaded because the conditions exist for the vast majority of rational economic actors to want to hedge against the currency. To focus one’s energies in such circumstances on the smaller number of actors with the financial heft, risk appetite and risk capital to profit from the situation is distracting.

The Black Market & Market Manipulation

Of course, the government should seek to enforce the law against black market operators and use whatever moral suasion and policy tools are at its disposal to discourage destabilizing speculation. The issue is the degree of emphasis.

The black market – destabilizing speculation nexus in Ghana has been tackled entirely at the retail market end by the authorities. They have organized mass arrests of street-level dealers in recent weeks, for instance.

The problem is that this segment of the forex market is an overflow from the forex bureau market. Forex bureau trades are only 1.2 percent of the total forex transaction volume in Ghana, down from roughly 4% seven years ago. The commercial banks mobilise 72.5% of forex and handle 98%+ of mass market sales. As we have explained extensively elsewhere, the commercial banking sector is now too dominant in the forex trade for small upticks in government forex reserves from such limited inflows as the opaque Afreximbank facility and syndicated cocoa loans to make a significant impact. A two billion dollar injection cannot override sentiment in a near $40 billion system if things are going downhill.

The annual Eurobond injections, on the other hand, were critical because in addition to boosting confidence they were also leveraged for a wide range of liquidity swaps that provided buffers and cushions throughout the year buoying the more vital commercial bank-level trade. With those elements sadly out of the picture, the critical focus should be on taking actions, such as discussed later in this essay, that will sustain commercial banking forex sentiment.

Concern about traders from neighboring countries using Ghana as a hub for obtaining dollars is interesting but if such a trend is significant it must correspond to an increased demand for Naira and CFA in Ghana, which would mean that the fundamental driver of rates would be trade not speculation. Put another way, it would mean that Ghana has started importing such large quantities of goods from across the sub-region that forex operators here are willing to offer large volumes of dollars to secure Naira and CFA.

Given Ghana’s overall higher international trade surpluses, any such sub-regional trade dynamics must be marginal.

The Thrust of the Forex Market

That last point is very significant. On the trade front, Ghana is one of the best performing in the region from the perspective of net dollar/forex importation through the trade channel. Since discovering oil and from the onset of the gold boom, Ghana has been piling up trade surpluses. Yet, its overall current account has been under significant pressure. When that happens it means that the hard currency is being repatriated out of the country for reasons other than basic trade.

In Ghana’s case, the real “culprits” are actually not too difficult to find.

Over the last decade, the country has been aggressively liberalizing its capital markets. The government has tried to attract a lot of capital into the country by promising investors that it will be easy to repatriate their profits and principal back home whenever they want. A fair bargain, especially when times are good.

Amidst groundbreaking developments like launching, in 2017, Africa’s largest domestic bond priced in dollars and targeting mostly foreign investors, Ghana has been busy promoting direct equity investments into all sectors of its economy. Much of the growth touted by the government and visible signs of affluence in the capital come from these liberal flows of forex-denominated capital. Many corporate institutions in Ghana became very focused on raising both debt and equity overseas by riding on the broader narrative, pushed in no small part by the government, of fast growth, super high returns, and liberal capital rules.

And the government took a big chunk of the flows. Let’s even put aside the country’s Africa-topping Eurobond issuances (as a percentage of GDP) in the international capital markets. At one point, the country ranked fifth in the world for how high a proportion of its domestic government debt had been bought by foreigners.

On the whole, whether forex or cedi-based, the fixed income market that started life in 2015 with barely 5 billion GHS in trading volume and is now the fastest growing in Africa (total volume heading towards 300 billion GHS) is totally dominated by investors trying to lend at very high rates to the government.

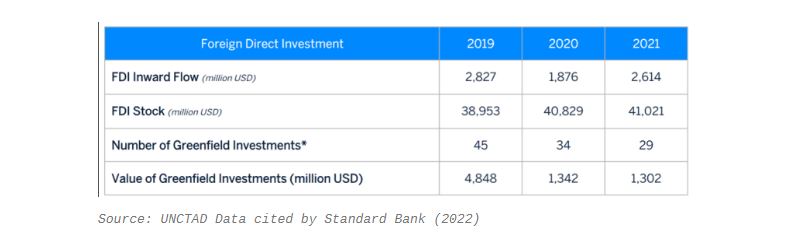

Government-fueled capital inflows mirror considerable growth in overall Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in Ghana.

If the government’s own numbers are to be believed, FDI inflows have grown from $20 million in 1991 to $115 million in 2000 to $2.6 billion today. The total FDI stock is a staggering ~75% to ~80% of GDP compared to a continental average of about 25%. Even if we significantly discounts the government’s numbers, the ratio is still intimidating.

It is widely accepted that any country with an FDI-stock-to-GDP ratio above 40% is highly vulnerable to global shifts in sentiment about their economy. The equivalent numbers for Cote D’Ivoire, Nigeria, and Kenya, for instance, are 22%, 25%, and 18% respectively.

Because of the pivotal role played by the government in maintaining this entire apparatus of liberalized capital flows, its continued fiscal adventurism, and the damage it has caused to its credit-worthiness, has sent shockwaves throughout all parts of the economy exposed to global investors.

Foreign investors have dumped 10 billion GHS worth of government bonds and bills this year, but the problem is that they can’t find enough dollars to sell more of the 11% of total stock they still hold. Various other investors have been trying to exit other investors early and quite a number have suspended planned projects. The resultant impact on forex flows in Ghana is self-apparent.

To be absolutely clear, the commercial banking forex window, the dominant part of the forex market, is where all this plays out and not in the forex bureaus and street-level black markets.

So long as various major economic actors are making rational decisions about preserving the value of their investments, they will seek to exit Cedi assets with resulting pressure on the exchange rate. The way forward is for the government to truly and proactively restructure its entire spending in order to drastically reduce the fiscal deficit and stop further monetization. A wholesale end to the decrepit and highly corrupt procurement system that have spawned such woeful cases such as Kelni GVG and underhand SOE commercial dealings such as the GNPC-Genser contract is important to convince analysts about the sustainability of such measures.

Racking up arrears rather than removing obligations, as the government has been currently doing, simply prolongs the problem because sooner than later it would be forced to pay the power plants some of their mounting piles of unpaid invoices (one major producer was recently sent a cheque for $5 million as a sop to keep the lights on despite arrears of roughly $150 million); do right by the medicine and food suppliers of the now totally socialized health and education sectors; and face up to its unkept promises to road contractors else watch them pack up and leave like it happened with the botched National Cathedral project.

The fiscal drag from the casino capitalism days continues to generate negative currents throughout the economy, heavily undermining confidence. If such is allowed to persist, even as inflation and other direct effects multiply, another phase of exchange rate depreciation might open up that will be even less responsive to policy measures.

But what about the IMF deal?

The IMF Deal

This author and his collaborators have written extensively about the ongoing negotiations between Ghana and the Fund.

The crux of the matter is that when in 2021 the World Bank and the IMF said Ghana’s debt was sustainable but at high risk of distress their assessment was based on several caveats:

- Not considering energy sector and cocoa sector liabilities, among others.

- Assuming continued access to borrow from the Eurobond market.

- Assuming steady cost of borrowing.

- Trajectory of debt falling under the thresholds in the standard Debt Sustainability Analysis (DSA) framework.

All those caveats no longer hold. By the yardsticks openly used by the IMF, it is apparent that Ghana’s debt is unsustainable going forward under current fiscal policies.

There are therefore only two serious questions:

- Can public debt be made sustainable without a debt restructuring?

- Will debt restructuring be made a “prior action”, i.e. prerequisite, before the IMF offers Ghana a deal?

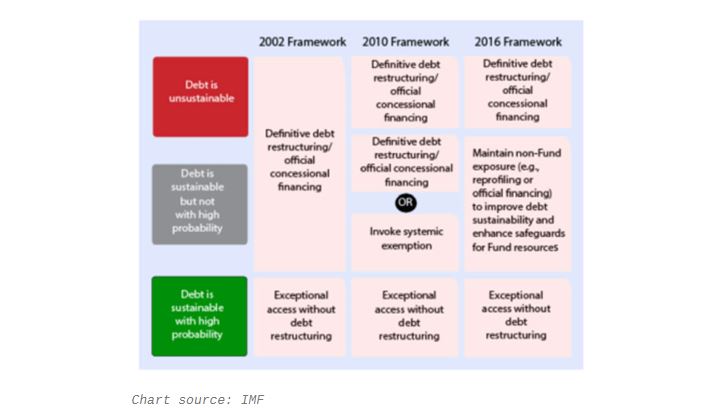

Under newer rules in place since 2016, a country with unsustainable debt seeking an IMF program is not automatically required to restructure their debt. But they must find substantial concessional finance if restructuring is to be avoided.

Given Ghana’s large gross financing needs, recent announcements by the country’s Finance Minister of interest on the part of Germany and France to step in with concessional financing are not sufficient. Ghana is far past the stage where bilateral funding can be arranged quickly enough and in quantities capable of making a difference. This means that debt restructuring is inevitable in the course of an IMF program.

True, there are exceptional access policies that sometimes allow the IMF to continue lending to a country with unsustainable debt. But such facilities are far more likely to be used when the country has already started receiving funds from an IMF facility and continued lending is thus judged to be necessary to safeguard the IMF’s already committed resources.

The “Prior Action” Bogey

The only serious questions then are whether the Fund will make such restructuring a “prior action” and if they did whether the government has the political muscle to commence the process without a hitch before later signing an IMF deal, and then using the new flow of resources and enhanced credibility to address the ramifications of the restructuring program. All prior actions are required to be completed five days before the IMF Board is expected to meet to approve a program with a member state.

Analysts worry about prior actions generally because they would mean delaying the commencement of an IMF program. In the case of a debt restructuring Prior Action, this would mean for certain that the government’s arbitrary November budget timeline would be breached. Simply because even the fastest market-friendly debt restructuring processes, once the roadshow has commenced, take about 3 months to close (example: Uruguay’s 2003 exercise). Considering how much the government has banked its hopes on an IMF deal, such a delay would be considered catastrophic by its dealmakers. And yet, the signs are not too rosy.

Still, Ghana has considerable goodwill at the top of the IMF, especially at the political level. Unlike various countries around the world, its record in recent years has been excellent with the Fund. The country is current on all its IMF payment obligations. Every one of its failures to meet targets set in previous programs (2009 – 2012 and 2015 – 2019) were sanctioned by the IMF itself through the latter’s own waiver procedures. Usually, the Fund does not require prior actions of countries that do not have an adverse record. But there is another factor that can make prior actions necessary notwithstanding excellent relations: country ownership of the planned program.

Where it becomes evident that a country borrower is not itself fully braced to take responsibility for the requirements and consequences of its own reform agenda, on the basis of which it is seeking IMF support, the Fund will normally insist on prior actions as a means of demonstrating real ownership. After all, an IMF program is merely meant to give spine to a domestically developed and steered program. Some countries like Belize have in the past even undertaken their own debt restructuring program without embedding it in an IMF program.

Ghana Hires a Sovereign Debt Restructuring Specialist

It is in the above context that news of Ghana hiring Paris-based Global Sovereign Advisory founded by a former Rothschilds banker is somewhat ominous. I will explain.

In 2020, the IMF cancelled a Malawi program due to the authorities providing false data, a strong sign of lack of sincerity about the country following its own commitments. When Malawi’s new government tried to rebuild ties and secure a new IMF program, it was advised to get a serious sovereign debt consultant on board. So, the country hired the same Global Sovereign Advisory (GSA). GSA then advised Malawi to restructure its debt ahead of a program with the Fund but the country balked. Since then, negotiations with the IMF have slowed. One wonders therefore whether the involvement of certain private sovereign debt specialists only becomes necessary when it is clear that debt restructuring is inevitable.

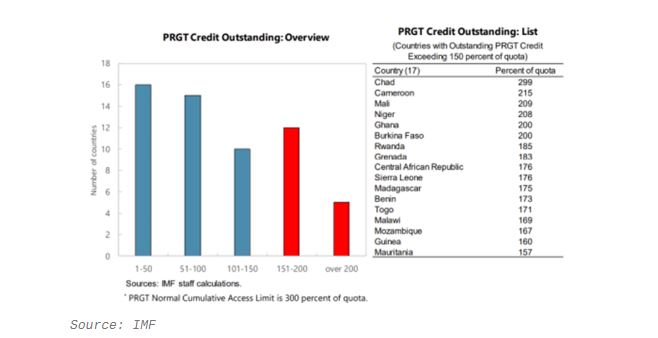

It is important to bear in mind that Malawi’s debt service to revenue ratio (how much of the government’s money spent on paying off debt) was pegged at 24.9% in 2020 when the country’s debt was judged to be unsustainable and a debt restructuring prior action demanded. Its debt to GDP was also around 60%.

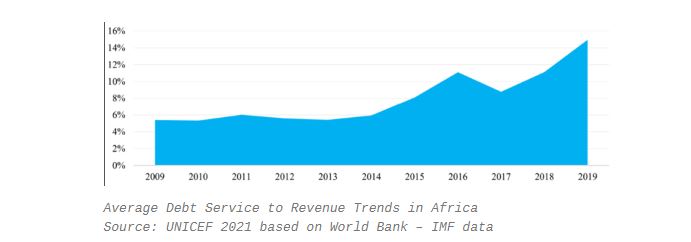

Ghana’s current debt service to revenue ratio is topping 60%. Its debt to GDP is between 85% and 110% (against the 55% threshold advised by the IMF) depending on which debts and arrears one chooses to add. Judged by a continental average of about 16% debt service to revenue ratio and 63% debt to GDP metric, one might be tempted to believe that the involvement of GSA is further evidence of the likelihood of debt restructuring being made a prior action.

The counter to that logic, as already hinted, is Ghana’s excellent record with the Fund and the belief that it has a higher debt carrying capacity than countries like Malawi. In those circumstances, the IMF could decide to let the debt restructuring process happen as part of the program rather than as a precondition for one. It will then use the “performance criteria” route to make debt restructuring a condition before the first disbursement of funds under the program.

But if it does not? If it insists on debt restructuring as a Prior Action as it did in the case of Jamaica and is doing in the case of Malawi? What about other difficult prior actions like privatising various debt-prone State-owned enterprises (SOEs), as it once did in Zambia’s case?

Ghana Should Not Set Up the IMF Program to Fail

Ghana’s excellent working relationship with the Bretton Woods institutions has survived many historical ups and downs. Occasionally the country has been judged to be less than candid about its affairs but when caught out, it quickly makes amends and apologises profusely.

It would be a monumental tragedy for the leadership were that track record to be broken as a result of this latest program.

The title of this essay points to the author’s worry, based on what has happened so far, about the government’s capacity to deftly handle the IMF program negotiation and design as part of its efforts to contain the current crisis speedily and with an eye on implementation success.

As clearly argued in an earlier essay, any domestic debt restructuring activity (domestic debt prioritization is essential because it provides 75% of the government’s short to medium-term liquidity relief) shall require tremendous amounts of public goodwill and the full collaboration of the political opposition.

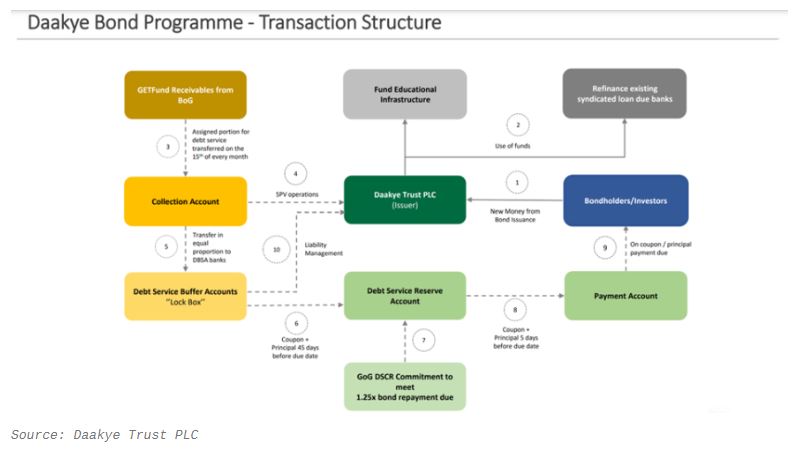

To avoid potential litigation and other confusions (such as may result from any attempts to exempt certain categories of creditors such as households or obstruct certain trades without damaging the Repos markets), new laws are likely to be required to smoothly execute any domestic debt restructuring.

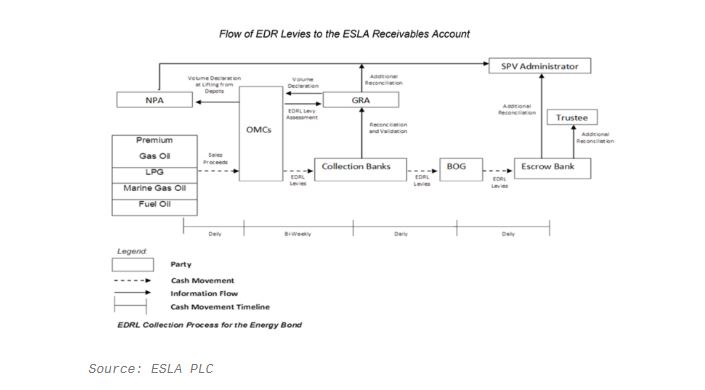

Some readers may not be aware that one of the effects of the securitization models used by the government to ramp up borrowing in recent years has been the nominal transfer of government debt to non-government special purpose vehicles with the debt collateralized (and in some cases overcollateralised) with future tax flows. An investor could conceivably garnish the accounts of the government in the event of any coercive restructuring. One of these special purpose vehicles, ESLA PLC, is even subject to English, rather than Ghanaian, law.

Unpacking all of this complexity to pass the right legislative measures will require consensus in the effectively hung and fiercely polarized Ghanaian parliament.

To garner credibility with the markets, restructuring would also have to be deep enough else Ghana risks seeing a situation similar to Jamaica’s 2010 to 2013 episodes, where an additional restructuring was required to hit 30% (8.5% of GDP) relief after the first one failed to go far enough (achieving relief equivalent to only 3.5% of GDP). On top of that, the IMF insisted that all bond holders must be covered (i.e. “100% participation”) before it would approve. Jamaica’s second restructuring case was in such trying circumstances only successful due to very skilled management and a bold decision to create a local creditor committee with unfettered access to all data shared with the IMF in the ensuing part two program.

The simple truth is that the short-term effects of any debt treatment that achieves 30% liquidity relief for the government and bring debt service to GDP ratio below 40% in Ghana would also have substantial effects on liquidity in the funds industry and may well rout the domestic fixed income market by curtailing participation for a while. A government shut from the international markets would now struggle to borrow locally too.

Exempting businesses and households from the debt treatment in order to conserve political capital means an even greater burden for banks and Funds. Because quite a number of the banks would require capitalization in such a situation, and yet direct resources from the IMF ($1 billion per year in the most optimistic scenario) would be far from enough to tackle the resultant effects.

The $3 billion that Ghana has requested will take its already high extra-quota access to a level that under IMF policies normally require “heightened scrutiny”.

And yet, it remains a small fraction of the $15 billion needed over the same period to cushion against the effects of adjustment. The restructuring would create far more problems than it would solve if it does not contribute to a broader program to restore investor confidence across the board and unlock much greater additional resources.

Ghana must be guided by the famous saga of the botched debt restructuring program in Russia in 1998 that triggered a currency run after investors judged that the overall program will not result in debt sustainability. Actors that shape sentiment in such contexts, especially in the political opposition, need close cultivation and briefing at every point.

Even an Approved IMF Program Does Not Guarantee Success

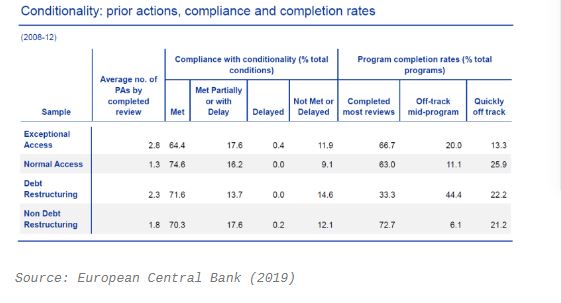

After all, a detailed analysis of many IMF programs between 2011 and 2017 found that only 32% achieve success. Unsurprisingly, programs that involve some debt structuring or relief tended to be more successful though only 33% of such programs proceed to completion. Countries like Pakistan have today become bywords for serial IMF recidivism because each program becomes protracted.

Still, whatever its historic sins, scapegoating the IMF should no longer be used as an automatic get-out-of-jail card for fiscally bumbling African states.

The government of Ghana must take full responsibility for the path it is taking the country on. Which is why some analysts worry seriously about whether the current decision makers at the helm have what it takes to build the degree of public goodwill necessary for the hard choices facing the country. There is a secretiveness, a clannishness, an aloofness and a pervasive lack of accountability that alienates rather than mobilises. In good times these may well be the ingredients of success in the private capital markets. But in a context such as the one Ghana currently finds itself in, it is highly counterproductive. To date, the government has not even published the so-called “enhanced fiscal recovery program” based on which it is purporting to negotiate with the IMF. Very much the opposite of what the authorities did in countries seen to have had a relatively successful debt restructuring exercise like Uruguay and Jamaica.

Besides all the technical complexities described in this essay, the lack of political preparation for the serious development ahead of Ghana in containing the current economic crisis is, to the greatest extent, what keeps this author awake at night.