Juma Hamisi, not his real name, keeps his distance, careful not to trespass, as he points to mounds of rubble spread across an open field. They are signs that a thriving community once lived here in a mix of concrete and grass-thatched mud houses.

At this time of year, the surrounding fertile land would normally be covered with a variety of sprouting crops – enough to feed the village, along with a surplus to sell at local markets. But it too lies bare.

“We used to be the source of cassava and lemons, now there’s scarcity. We can’t even harvest the coconuts you see over there because it’s not our land any more,” Mr Hamisi says.

Several signs bearing the name Tanzania Petroleum Development Cooperation, a state agency, now claim ownership of the area where villagers once lived, farmed and played.

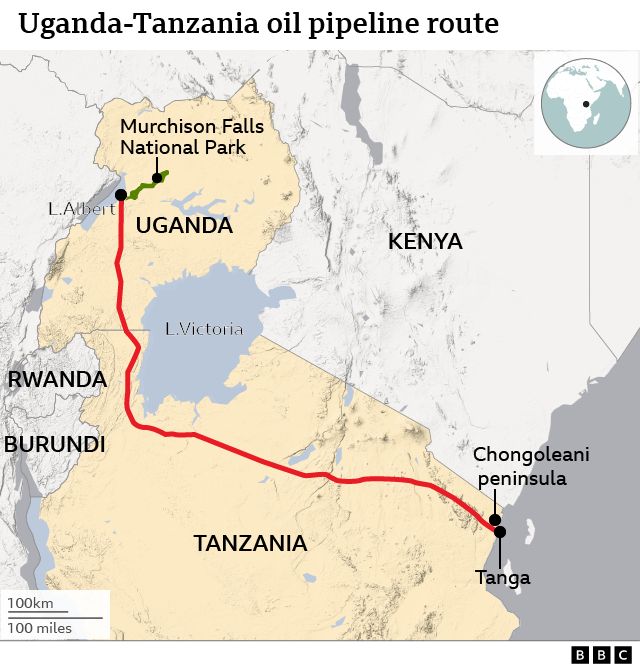

Some of the inhabitants of the Chongoleani peninsula, some 18km (11 miles) north of Tanzania’s port city of Tanga, sold their land for compensation two years ago, after the government signed a deal to construct a pipeline to transport crude oil from the shores of Lake Albert in western Uganda.

Eighty percent of the 1,440km- (895 mile) pipeline, whose construction will begin in a few months, will be in Tanzania including a terminal-storage facility in Chongoleani.

French energy giant Total Energies and Chinese energy firm CNOOC International also have a stake in the $5bn (£4bn) venture.

Because of the waxy nature of Lake Albert’s crude oil, it will be transported through a heated pipeline – the longest in the world. But only a third of the reserves of 6.5 billion barrels, first discovered in 2006, is deemed commercially viable.

Despite the projected economic benefits, the timing of the project has divided opinion in Uganda and beyond.

In September, the European Union waded into the controversy surrounding the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (Eacop), and called for it to be halted, citing human rights abuses and concern for the environment and the climate.

The intervention was dismissed by the Ugandan and Tanzanian governments which see the pipeline as vital to turbo-charge their economies.

“They are insufferable, so shallow, so egocentric, so wrong,” Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni said of the EU lawmakers.

His frustration is shared by some advocates of Africa’s economic development who argue that the continent has the right to use its fossil fuel riches to develop, just like rich nations have done for hundreds of years.

They point out that Africa has only emitted 3% of climate-warming gases compared to 17% from EU countries.

Crucially, 92% of Uganda’s energy already comes from renewable sources. In Tanzania, it is about 84%. Whereas for the EU it is 22%, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency.

“It’s hypocrisy,” Elison Karuhanga, a member of Uganda’s chamber of mines and petroleum, says of the EU’s comments about the pipeline.

“Unlike wealthy nations which will remain wealthy even when their oil and gas revenue is removed, we cannot afford to gamble the future of Ugandan generations on hypotheticals,” Mr Karuhanga says.

The first oil is expected to be tapped in three years with at least 230,000 barrels pumped out every day at its peak – projected to earn Uganda between $1.5bn-$3.5bn a year, 30-75% of its annual tax revenue. Tanzania will reportedly get at least $12 a barrel, close to $1bn a year.

Despite the estimated windfall, campaign group Stop Eacop says the pipeline will produce 34 million tonnes of harmful carbon emissions each year. It passes near Murchison Falls National Park, an area rich in biodiversity, as well as farmlands.

TotalEnergies, which has a 62% stake in Eacop, told the BBC that the project will have “one of the company’s lowest carbon dioxide emission levels”.

“The pipeline route was designed to minimise its impact on the landscape and biodiversity” and “will significantly improve living conditions locally,” the French oil giant said.

However, Ugandan climate activist Brian says Eacop would only turn Uganda into a “petrol station” for Europe and China and says the windfall from the project will only benefit the country’s elite. We are not giving Brian’s full name for security reasons.

Despite threats of arrest and harassment faced by Eacop opponents, Brian continues to campaign for the country to switch to green energy as it committed to by signing the Paris Climate agreement in 2015 – the global plan to prevent temperatures rising beyond 1.5C compared to pre-industrial levels.

“You only use the oil and gas that’s already developed. The moment you start developing new ones today, and tomorrow, and a month later and years from now, you’re delaying the process of transition, and that will cause a tipping-point for the climate,” Brian says.

Tony Tiyou, the head of the company Renewables in Africa, disagrees with green energy purists.

“I may be a renewable advocate, but I’m also a practical guy,” he says.

“I know we’re still going to need some fossil fuel because at the moment people need power in Africa and if they don’t have power, it will be a little bit difficult to lift people out of poverty,” Mr Tiyou says.

“Solar and wind could be intermittent. You don’t have solar at night, for example, and wind doesn’t always blow when you need it. But people talk about an energy mix – a combination of different sources.”

We have asked for comment from the Tanzania and Uganda governments.

But despite the urgency for energy transition as set out in the Paris agreement, global investments in fossil fuels still outpace those in renewables.

“Part of the reason is the fact that you need to look at who’s going to benefit from the project, because you can’t really export renewable at this stage, you most of the time, use it locally. You can export oil, and guess who’s going to benefit from that?” Mr Tiyou says, referring to Western countries.

It’s a point that Faten Agaad, senior adviser on Climate Diplomacy and Geopolitics for the African Climate Foundation, agrees with.

“African countries are not receiving financing required for the green transition. That’s why we see countries turning to fossil fuels as a way to generate incomes. I mean as we speak, the financing of fossil fuels is three times higher than for green energy, that’s $30bn to $9bn for renewables.”

She also accuses the EU of hypocrisy.

Although Eacop plans to construct a refinery in Uganda for domestic consumption, its crude oil will mainly be for export, especially for Europe as a result of the ripple-effects of the war in Ukraine.

While Uganda hopes to benefit from its oil well into the future, this may not prove to be the case.

“What we’re seeing is that Europe is working towards a transition, and in fact, not just in Europe. Even in Asia. China is currently the largest in terms of solar capacity, we also see other large economies like Indonesia also transitioning. So the risk for African countries is in 20, 30, 40 years they’ll find themselves with assets that are not a good return on investment,” Ms Aggad says.

How to balance economic development as well as fight climate change will dominate discussions at next month’s Cop 27 conference in Egypt.

Activists from developing countries have been putting pressure on rich nations to honour their commitment at Cop 26 last year for urgent funding for climate adaptation and mitigation projects, as well as to compensate them for the loss and damage that they have wrought on the planet while building their own economies.

Back in Chongoleani, several unfinished concrete houses dot an area near where villagers who sold their land were relocated. They complain that the compensation given was not enough. Some are said to have invested their money in new businesses which have since failed.

Others said they had taken up fishing after farming became untenable.

Meanwhile, newcomers from other parts of the country continue to arrive in the area hoping to benefit from the project.

Mr Hamisi, like many in the community, hopes that the oil pipeline project will help replace his lost farming income, and bring prosperity to the village.