Alhaji Iddrisu Dabuo, 71, leaves his home at 8 am on Thursday, September 14, 2022, to his 10-acre sorghum farm, which is just a few steps away.

The good-looking crop has only been growing for two months since it was planted, and Alhaji Dabuo is waiting another month until the top half of the head has turned brown and the lower portion is no longer green, which are clear signs that it is time to harvest.

Shattering will occur if he waits too long to harvest, and Alhaji Dabuo will probably lose more seeds as a result than if he had harvested too early.

There are no signs of pests, diseases, or nutritional deficiencies, and the leaves are firm and the flower systems are well-developed.

He visits the farm every day to keep an eye on any challenges and to act if necessary to protect his investment.

In the Upper West region of Ghana’s Chapuri community, there hasn’t been any significant rainfall for roughly three weeks, but the 71-year-old farmer is delighted with how well his crops are thriving despite the challenging weather.

Temperatures are rising, resulting in drier soils. Ground-level drying has increased as high air temperatures sap liquid water from soils and plant leaves. This not only encourages the development of drought conditions in the area, but also intensifies the impacts.

As more intense droughts coincide with the trends of rising temperatures and decreasing rainfall, the more Alhaji Dabuo points to the impacts of climate change.

Since 2010, the former subsistence maize farmer who only grew enough to feed his family and sold the surplus has shifted to sorghum – a drought-tolerant crop that does not require expensive inputs such as fertilizer to generate strong yields.

Alhaji Dabuo said he plants his own sorghum seeds which he stores for subsequent seasons – a decision he believes is something good farmers should do.

“Farmers shouldn’t rely on corporations for their seed needs. Why should they depend on the farm for a living while neglecting to save seeds for later seasons? Any farmer who doesn’t save seeds for future harvests isn’t one,” he said.

“LOST CROPS” PART OF LOCAL ADAPTATION ACTION

Alhaji Dabuo’s switch to sorghum is part of a wider move by farmers to embrace so-called “lost crops” from decades past and implement their own locally-led adaptations to the unpredictable weather linked to climate change.

In the past, Chapuri farmers like Alhaji Dabuo were able to predict the onset of rains, but that is very difficult now due to shifting weather patterns. Unpredictable rainfall patterns can have a major impact because a large portion of the area’s farm output relies on reliable rainfall.

As it becomes increasingly difficult to predict when the rains will begin and end, farmers are racing against the clock during the crop season, unsure of the best times to plant or harvest crops.

“It’s impossible to predict when it will rain and when it will cease. The peak of the rainy season is impossible to predict,” said Jirapa Municipal’s Management Information System officer, Adams Alhassan Waahu.

The district, like the rest of northern Ghana, has only one rainy season, which runs from May to September. However, even this pattern is no longer guaranteed, as delays or the early cessations of rains have become the norm in recent years.

“This is exactly what we’re going through right now. Rain does not arrive on time, but it leaves earlier than expected. As a result, massive crop failures occur, particularly in maize,” Alhaji Dabuo said.

He was perplexed and when the rain did not arrive as expected, the maize crops would either wilt or perish early. This required him to replant in the vain hope that the rains would turn favourable again.

“We no longer comprehend the pattern of rainfall, and rains stop suddenly,” he said.

The reduced maize output — when coupled with the rising cost of farm inputs such as agrochemicals and fertilizer — meant Alhaji Dabuo saw little to no profit at the end of the crop season.

After one of these seasons of only growing maize, he had revenue of about 2000 cedis but spent at least 1500 cedis on inputs for one acre of land. As a result, his profit of roughly 4,500 cedis from 10 acres of farmland was not enough to recoup his initial investment plus the cost of inputs.

Rising input costs could put his investment well above the norm, and when coupled with bad weather, Alhaji Dabuo either loses the crop to weather or it does not deliver a productive yield. At the end of a season, he sometimes struggled to pay himself and his workers with the slim profit. It led Alhaji Dabuo to reconsider the crops he grows.

“In farming maize, we occasionally have good yields but lower profits. We all decided to start farming sorghum because of how profitable it is,” he said.

Sorghum is more profitable per acre when compared to the maize he grew years ago. It also provides a more reliable revenue stream to pay his workers.

“I actually depend heavily on labor to cultivate my crops,”Alhaji Dabuo said.

In 2017, the price earned for 50 kg of sorghum was 65 cedis, compared to 30 cedis to the same size of maize. But Alhaji Dabuo said his profit and loss analysis showed he still came out ahead by growing sorghum as his losses would have been higher if he had stayed with maize.

Since then the profit margin between these two crops has risen. In 2021, 50 kg of sorghum was sold at 85 cedis while 50 kg of maize was going at 50 cedis.

According to Alhaji Dabuo, 2022 is a promising year because the cost of 50 kg of sorghum is expected to be 200 cedis. He is thrilled that his crops are flourishing and will bring in the highest profit ever.

“I made the right choice to return to whatever we had previously planted. If I hadn’t made up his mind in 2010, I can’t begin to fathom how miserable his life would have been,” he said.

Alhaji Dabuo, a lifelong farmer with three wives and 21 children, said the farm has been their only source of income. He noted that 11 of his children now live and work in Accra and the capital Kumasi.

While some of them are already married, Alhaji Dabuo used the farm income to help the others learn a trade in the cities.

Sorghum was a game changer for the family.

In 2019, it enabled Alhaji Dabuo to build a six-bedroom house in three years for only 30,640 cedis.

SORGHUM VS MAIZE IN NORTHERN GHANA

Sorghum and other grass family crops were commonly grown in northern Ghana, while maize (Zea mays) was originally a major cereal staple in the south. Maize benefited from donor support for research, crop promotion and other enhancement activities over traditional cereals such sorghum and millet. As a result, maize cultivation extended into northern parts of the country.

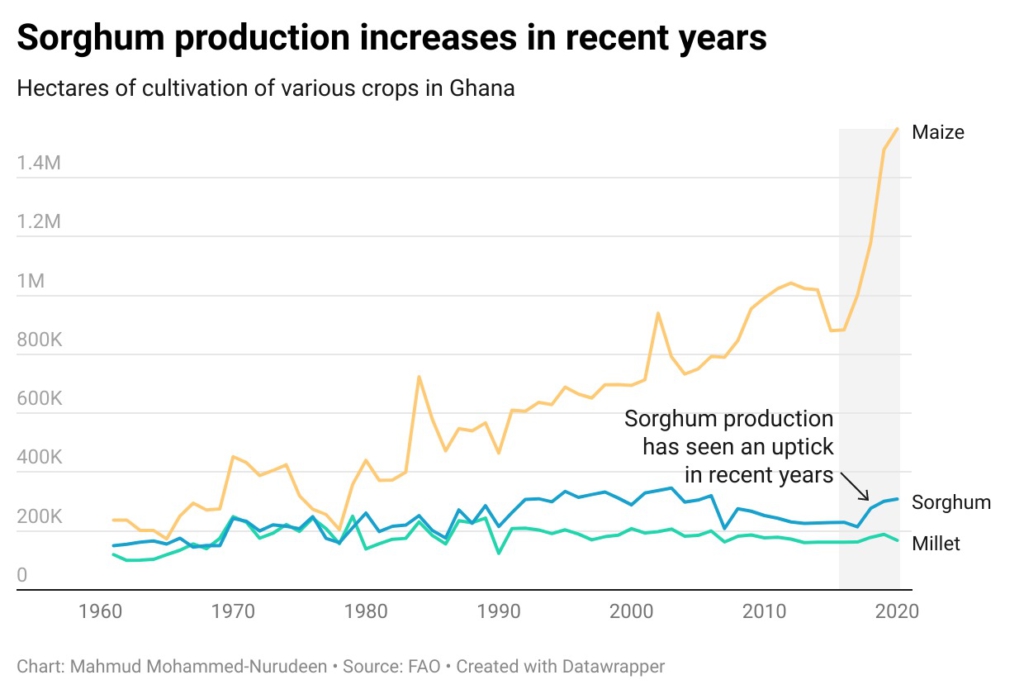

However, in recent years, sorghum cultivation has begun to pick up again after a decline in production from 2010 to 2016, according to Kenneth Opare-Obuobi, Sorghum breeder at the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research Institute of the Savanna Agricultural Research Institute (CSIR-SARI) –Nyankpala.

Farmers are returning to sorghum mainly due to the crop’s resilience to climate variabilities such as drought and high temperatures when compared to other grains such as maize and rice. The crop outperforms other cereals such as maize and rice in low fertility soils, Mr. Opare-Obuobi said.

Also, as sorghum is a raw material for the brewing industry, it is in growing demand as an industrial cash crop. Unlike other cereals, sorghum is a dual-purpose crop. A farmer can use its grains and stalks as human food and animal feed.

“The number of bags a farmer harvests from an acre of land is dependent on a number of factors such as the choice of variety and the agronomic practises employed, not forgetting environmental conditions such as rainfall,” Mr. Opare-Obuobi said.“Some improved varieties can yield as much as 16 – 20 bags per acre when all the agronomic requirements are met,” he added.

The use of landraces (mostly inherently low in yield) and the culture of using recycled seeds in season after season be avoided, he said.

He encourages farmers to use seeds of improved varieties that have been tested and verified as high yielding by an accredited seed retailer to ensure they improve a farmers’ yield.

“Farmers should seek technical advice and assistance from the experts,” he advised.

The CSIR-SARI is an institution mandated to help farmers to improve upon their crop production, especially the traditional cereals, and soil management practices.

“CLIMATE CHANGE HAS NO EFFECT ON SORGHUM”

Abdallah Amadu Tijani, 34 and among the young farmers in Chapuri who have switched to sorghum since 2012, said the crop is profitable and has a market.

Mr. Tijani cultivated ten acres of sorghum and harvested 100 bags in 2021.It inspired him to double his sorghum plantingsto 20 acres this year.

“I’m aiming for 250 to 300 bags of sorghum,” he said in predicting the size of his 2022 crop,” he said.

Like Alhaji Dabuo, Mr. Tijani said producing maize was capital intensive and access to available markets was challenging. Sorghum’s resilience to climate-driven weather impacts was also a factor in his decision to switch crops.

“Climate change has no effect on sorghum as it does on maize,” Mr. Tijani said, adding that unpredictable rainfall meant some farmers were unable to plant maize earlier than expected.

Mr. Tijani does not add fertilizer to his sorghum crops, and he said other farmers in his area do the same and still get good yields.

In Chapuri, where 99 women are among the community’s 479 farmers, nearly every resident grew sorghum in 2022, according to the district’s department of agriculture. Sorghum was planted on1015 acres of farmland in Chapuri, compared to 500 acres of maize and 200 acres of rice.

Sabrokoe Eunice, 45, and 47-year-old Mankama Hawawu — two female growers who farm three and five acres of land respectively — are also seeing success with sorghum and earning enough profit to support their families.

The return of sorghum has also sparked a revival in recipes using the venerable crop. For example, TZ, also known as Tuo Zaafi, is a popular food in Ghana and parts of West Africa where it is made from millet, sorghum or maize.

“We use Sorghum to make TZ and porridge, among other things,” said Azara.

Also, the proceeds from the sale of sorghum are received earlier than the proceeds from the sale of maize. The earlier payment can be used to pay children’s school fees, they said.

Both women have been cultivating sorghum for the past ten years because of its ability to withstand any type of bad weather. And because there is a ready market for sorghum, most farmers in Chapuri sell their grains after harvest through the Ghana Commodity Exchange (GCX), the open market and aggregators who supply to industry including Guinness Ghana.

SORGHUM TAKES OFF IN NORTHERN JIRAPA DISTRICT

In Jirapa District, some 85 percent of its 91,279 people are farmers, according to the 2021 population and housing census, and about half of the district’s farmers are growing sorghum as a staple crop.

Sorghum is the second most important crop grown in Jirapa after the grass crop millet, according to the Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MoFA) website.

Sorghum plantings fell from 16, 180 hectares to 11,826 hectares in the period from 2003 to 2008. During the same period, millet also fell from 21, 550 to 11, 453hectares.

Despite the fact that millet production increased to 12,800 hectares in 2009, the year was significant for sorghum. Cultivation increased by 24.3% to 14,700 hectares, while millet increased by 11.8%.

During the same 2003-2009 period, maize covered between 2, 612 and 3, 410 hectares, while rice covered between 550 and 900 hectares.

According to FAO statistics, from 2010 to 2016, national production of sorghum decreased while crops such as maize increased until 2017, when sorghum began to increase until now. Sorghum production, for example, ranged between 229,604 and 324,422 metric tons between 2010 and 2016. Between 2017 and 2020, the figure increased from 230, 000 to 356,000 metric tons.

These trends suggest sorghum is becoming a cash crop in Jirapa District, said Oteng Samuel, a former agricultural director for the district.

Sorghum is a good source of energy and is not polished like rice, he said, adding “it is a whole grain with carbohydrates and fiber that is beneficial to our system.”

However, one major challenge is variety, because farmers use their own stock every season, Oteng Samuel said.

HOW SORGHUM RESISTS DROUGHT, OTHER HARSH CONDITIONS

The doughty nature of sorghum stems from a number of factors, including its root system. Sorghum roots can reachas deep as 2.5 m below the soil surface where most crops, including cereals like maize and rice, cannot reach even half that depth, said Mr. Opare-Obuobi.

“Secondly, the secondary roots which are the main receptors for moisture and nutrients are more per unit primary root in sorghum compared to other cereals,” he added.

“This attribute of the crop gives it the ability to tap moisture and nutrient deep below the soil surface where most cereals cannot reach thus its droughty nature as a crop.”

He said most sorghum varieties have a waxy bloom substance that covers the leaves and stems. This minimises the rate of moisture loss from the plant through transpiration, a process that allows the plant to cool down when temperatures rise.

Sorghum leaves can move upright and roll when stressed by water. This reduces the amount of leaf surface area exposed to solar radiation, further reducing the rate of moisture loss by the plant. Sorghum plants naturally drop their lower and older leaves during periods of water stress and during grain filling, allowing the crop to retain output under severe stress.

NUTRITION FACTS OF SORGHUM

Half (½) cup (96 g) raw sorghum (dry and uncooked) according to USDA contains;

Calories: 316

Fat: 3g

Sodium: 2mg

Carbohydrates: 69g

Fiber: 7.5g

Sugars: 2.5g

Protein: 10g

A ½ cup portion of the grain will turn into 1 ½ cups of cooked sorghum. Most people will likely eat only ½ cup to 1 cup cooked which will lower the calories and carbohydrate requirements.

Grain sorghum is high in micronutrients and outperforms several other grains in terms of nutrient density. One half-cup contains 18% of the Daily Value (DV) of iron, 25% of the DV of vitamin B6, 37% of the DV of magnesium, and 30% of the DV of copper. It also has high levels of phosphate, potassium, zinc, and thiamine.

Mr. Opare-Obuobi said the nutritional benefits of sorghum can aid food security in northern Ghana by addressing issues such as hidden hunger or micronutrient deficiencies, particularly in pregnant women and children under the age of five.

CROP DIVERSITY = FOOD SECURITY

Crop diversity is critical to food security in Ghana. A review of Ghana’s plant and genetic resources for food and agriculture suggests food security may be jeopardized if a national focus on only a few competitive crops, such as maize and rice, results in the continued decline of other crops, Mr. Opare-Obuobi said.

“Also, through the promotion of a few types of such crops, the phenomena have the potential to lead to genetic erosion of these few competitive crops,” he said.

FAO data shows that national production of sorghum fell between 2010 and 2016, while the output of other crops like maize and rice rose until 2017, when the sorghum started to make a comeback.

What could have been done to encourage farmers to grow sorghum and other grass family crops? Mr. Opare-Obuobi said there needs to be more study of these crops, along with the promotion of new and improved varieties to maximize a farmer’s output per unit area.

“Make seeds from these varieties available and accessible to all and promote them through farmer education activities, such as varietal demonstrations and exhibitions,” he said.

He said its critical forCSIR-SARI to produce early generation seeds of the existing commercial varieties, Kapaala and Dorado, as well as help designated and authorized certified seed producers in scaling up their seed production to meet the rising demand for sorghum seed.

“Support for farmer capacity building in grain sorghum production” is also needed to ensure potential yields of improved varieties are realised, he added.

HOW IS SORGHUM PROMOTED?

CSIR-SARI and Guinness Ghana PLC are conducting sorghum variety demonstrations in some districts in northern Ghana to educate farmers and promote the use of early-generation seeds of these improved varieties.

To increase sorghum production in the country, this will require the efforts of all stakeholders in the sorghum value chain through Public-Private Partnership (PPP) with industry, such as the Guinness Ghana/CSIR-SARI venture.

Mr. Tijani, the young farmer in Chapuri, said they are also training farmers in nearby communities such as Zaguo, Ping, Sabuli, Hain, Tuopari, Nindorwaala, Kenee, Olullo, Olulloku, Lulu, Nabre, and others on how to grow sorghum successfully.

More than 300 farmers have already been trained by their fellow Chapuri growers through demonstrations.

SNV-Ghana, an NGO with a focus on agriculture issues, sponsors the “TWO-Scale Project” in Ghana’s Upper East Region. The project is collaboration between CSIR-SARI and Faranaya Agribusiness Ltd, a commercial aggregator of sorghum.

The Garu-based project aims to increase sorghum seed production at all levels and ensure that farmers have access to all their seed requirementsto produce sorghum grains for industrial use.

Looking at the production and usage trends for this previously “lost crop”, Mr. Opare-Obuobi said he expected sorghum to be an important economic and food security crop in Ghana over the next five years, particularly in the country’s north where it is a traditional cereal. This, he said, will encourage medium and large-scale producers to invest in sorghum production in Ghana.

“In the next 5 years, we hope sorghum will be an important cash and food security crop in Ghana, especially in the northern part where is a traditional cereal. This will, in turn, motivate medium and large-scale producers to venture into sorghum production in the country,” he said.

–

This story was written and produced as part of a media skills development programme delivered by Thomson Reuters Foundation. The content is the sole responsibility of the author and the publisher.