As the Black Stars of Ghana prepare to face Brazil in a pre-World Cup friendly match on

Friday, the conversation has centred on Ghana’s sporting relations with the South

American country. Specifically, the game has been billed “The Brazil of Africa vs the Real

Brazil.”

Ghana’s moniker is a tribute to the special relationship that exists between these two sides, a

a relationship that was solidified in the 1960s, when Brazil dominated world football and

Ghana dominated African football.

But even before football entered the fray, the destinies of both countries had always been

intertwined, a family bond forged through shared struggle, dating back to the 19th century.

You see, Ghana is home to multi-generational descendants of freed slaves from Brazil who

returned to the continent following the Malê rebellion of 1835. Those that settled in the

Gold Coast (now Ghana), arriving in Jamestown, Accra, were led by Nii Azumah Nelson

(sounds familiar?) and came to be known as the Tabom people.

Through inter-marriage, they were gradually absorbed into the native Ga tribe, but it was

their industry that really endeared them to the locals. They introduced new skills in

agriculture, architecture, smithing, and carpentry that improved the quality of life of the

community in which they settled.

Their claim to fame, though, was in cloth-making, where they opened the first tailoring shop

in the country, tasked, notably, with providing the then national army with uniforms.

In the latter trade, a great son of the Tabom people found his industry, discovered a passion

and became arguably Ghana’s greatest sportsman – Azumah Nelson.

As history has taught us; a big proportion of the slaves taken across the Atlantic went to

Brazil, where slave trading was legitimate until 1888. Inadvertently, this has had an enormous influence on Brazilian culture: music, dance, and rituals, all of which have their roots in African traditions. Brazil is the most African country outside Africa.

It is why Vinicius Junior would break out with a dance to celebrate a goal; just as much as a

Ghana goal is not complete without the almost mandatory dance celebration.

And so, it would seem, Ghana and Brazil have always been a family affair.

The English brought the game to the Gold Coast, but it was the reign of a certain Brazilian –

Carlos Alberto Parreira, that ushered in the new era of Ghanaian football.

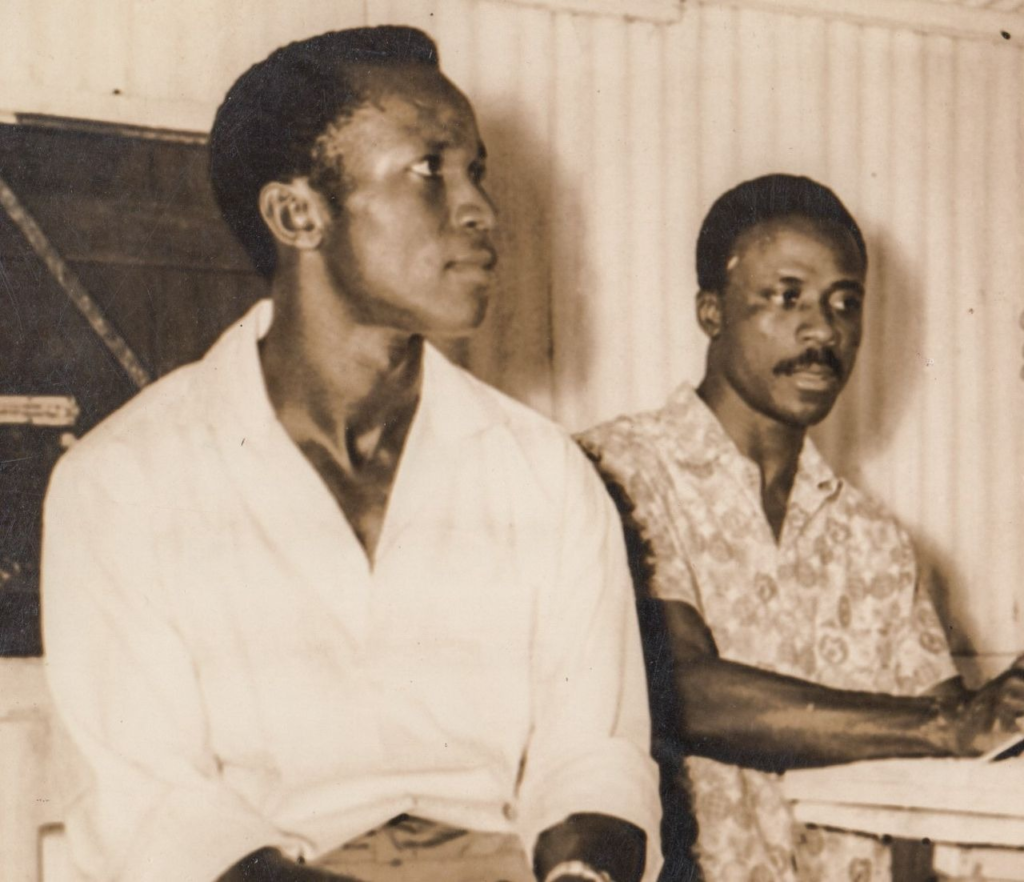

And all of it would not have happened, of course, without the legendary former Black Stars

captain CK Gyamfi.

The year was 1962 in Santiago, Chile, Mané Garrincha, had inspired Brazil to a second

successive FIFA World Cup trophy, playing some swashbuckling football along the way.

More than 5,000 miles east of the Atlantic, in a tiny apartment at Awudome Estate in Accra,

CK Gyamfi was preparing to leave Ghana for Brazil in pursuit of football knowledge.

Two years earlier, the late Gyamfi, had become the first Ghanaian to play professional

football abroad when he signed for Germany’s Fortuna Dusseldorf.

But having watched Pele’s Brazil dazzle the world in 1958 and 1962, Gyamfi was convinced

the only way to play football was the Brazil way.

The country’s first President, Kwame Nkrumah, and his indefatigable Director of Sports,

Ohene Djan, shared in Gyamfi’s vision about how Ghana needed to show the way in

football, just as they did in politics, by becoming the first country to attain independence in

the sub-region.

On his return in late 1962, Ghana was preparing to host the 1963 Africa Cup of Nations the

following year. “I hope Ghanaian players will learn from my experience,” he said on his

return.

Gyamfi made interesting observations from his trip to Brazil. First, most players in both

countries come from poor backgrounds where groups of children with no toys derive hours

of entertainment from playing with a ball or bundle of rags. Second, the good weather and

hours of daylight mean they do this often and third; the fact that many of the children are

sharing one ball means each makes the most of his turn. In other words, possession is the

chance for self expression.

But Gyamfi was particularly fascinated by one thing – tactics without the ball. Gyamfi

observed that Brazilians paid particular attention to position, and what each player did

without the ball. He concluded that if he could get Ghanaians to improve on that aspect,

they would become unbeatable.

József Ember had been in charge of the Black Stars before Gyamfi’s return, but the pan-

Africanist in Nkrumah, who had declared five years earlier that the “black man is capable of

managing his own affairs”, fired the Hungarian and Gyamfi was installed as the first black

coach of the Black Stars.

He led the team to Ghana’s first Afcon title, playing some scintillating football along the

way. And yet, there were a few dissenting voices, who took a chunk of the credit and

handed it to Ember for building the foundation that Gyamfi stood on to win the title.

But all of that doubt was put to bed in 1965, away in Tunisia, Ghana won a second

consecutive continental title. By then, there was no doubt whose team this really was.

Brazil won the 1958 and 1962 World Cup titles with the famous revolutionary formation, 4-

2-4, one that enabled the team to balance attack with defense. It marked the beginning of

the use of a flat back that has become the norm today.

And worked magic. Ghana stormed to victory unbeaten, scoring an astonishing 12 goals in

their 3 games at the competition.

Gyamfi’s team defined “winning with style” and sealed their reputation as Africa’s ultimate

“show boys”. And by mirroring not just Brazil’s style of football, but also their back-to-back

championship victories, the press deservedly crowned Ghana the “Brazil of Africa”.

When Gyamfi left the scene, he ensured the Brazilian-ness of Ghana’s team continued by

bringing in Parreira, a man Gyamfi met when he visited Brazil and interned at the University

of Rio. Parreira was then a young PE trainer who had studied English when he went to

Ghana and ended up landing his first job as a football coach. He was in his early twenties

then and remembers days of “camping in army tents”.

Parreira did not win the Afcon title of course, but he did come close, in 1968, when they lost

the final to DR Congo. That team, till date, is regarded by many as the best Black Stars team

to never win the Afcon.

Parreira did ultimately get his gold medal, except it was bigger, leading Brazil to the World

Cup crown in 1994. It was a victory many Ghanaians celebrated vicariously. After all, they

gave Parreira the platform to shape his ideas, a critical aspect of which being possession-

based football.

Somewhat, Ghana football has always been guided by the same principles. It is not winning,

if it’s not won in style. It is why many Ghanaians were happy to boast about outplaying

Parreira’s Brazil in 2006, despite losing 3-0 (and Parreira agreed with them when he said the

scoreline flattered his team). Ghanaians still take pride in drawing 2-2 with eventual 2014

World Champions Germany. After all, they were the only country to hold the Germans in

their all-conquering journey.

Armed with the same principles, Ghana’s games against Brazil have always been fascinating

spectacles. It is always adrenaline-filled affairs where the West Africans have often felt the

need to shed their “imposter syndrome” and prove that they too indeed, can play like Brazil.

That over-enthusiasm has so far proven counter-productive in four previous affairs, where

Ghana has lost every single one, with a combine scoreline that reads 13-2.

The Black Stars have also had a man sent off on each of those occasions with Emmanuel

Osei Kuffour (1996), Asamoah Gyan (2006), Haminu Dramani (2007) and Daniel Opare

(2011) all receiving marching others in previous encounters.

When they face each other again on Friday, September 23, 2022, it will not just a meeting of

two football nations preparing for the 2022 FIFA World Cup. It will be, just as with previous

encounters, a meeting of the same ideals, either side of the Atlantic, and the result, may not

matter after all.