The family of a father who was wrongly convicted of murder have been given a police apology 70 years after he was executed in a British prison.

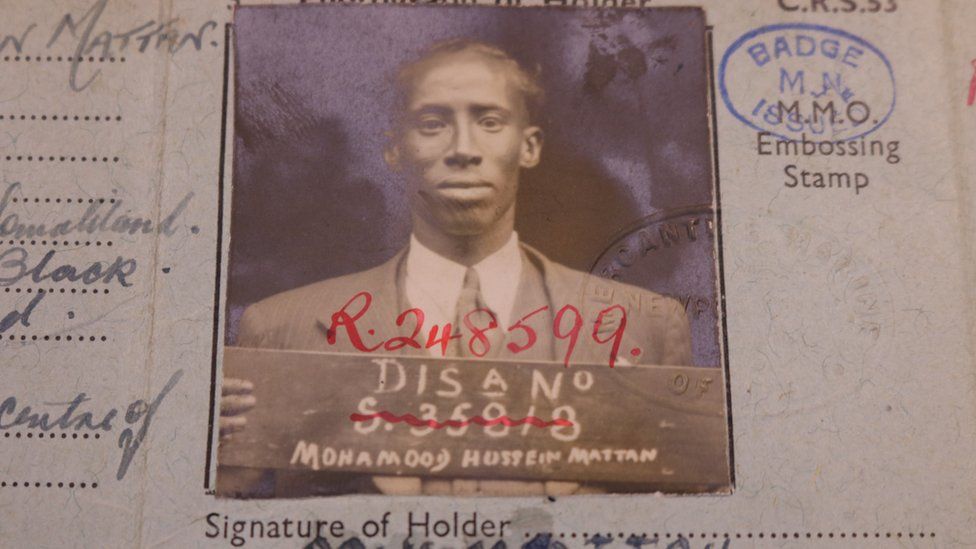

Mahmood Mattan, a British Somali and former seaman, was hanged in 1952 after he was convicted of killing shopkeeper Lily Volpert in her store in Cardiff.

His conviction was the first Criminal Case Review Commission referral to be quashed at the Court of Appeal in 1998.

South Wales Police have apologised and admitted the prosecution was “flawed”.

“This is a case very much of its time – racism, bias and prejudice would have been prevalent throughout society, including the criminal justice system,” said its chief constable, Jeremy Vaughan.

“There is no doubt that Mahmood Mattan was the victim of a miscarriage of justice as a result of a flawed prosecution, of which policing was clearly a part.

“It is right and proper that an apology is made on behalf of policing for what went so badly wrong in this case 70 years ago and for the terrible suffering of Mr Mattan’s family and all those affected by this tragedy for many years.”

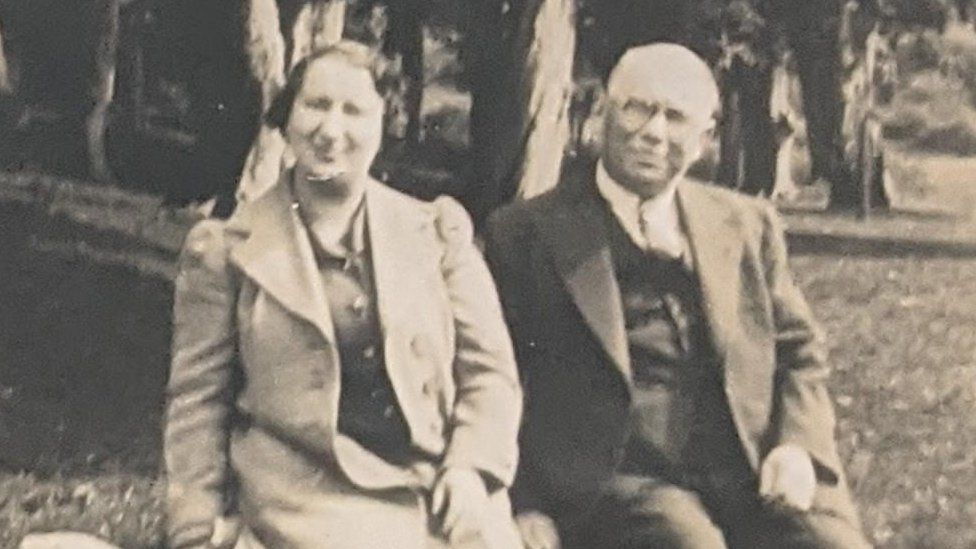

Mr Mattan’s wife Laura and their three sons David, Omar and Mervyn, who was also known as Eddie, campaigned for 46 years after his execution for his name to be cleared.

They have all since died and while the family welcomed an apology, one of his six grandchildren has called it “insincere.”

“It’s far too late for the people directly affected as they are no longer with us and still, we are yet to hear the words I am/we are sorry,” said granddaughter Tanya Mattan.

The Mattan family received compensation from the Home Office in 2001 but never had an apology from the police force until now.

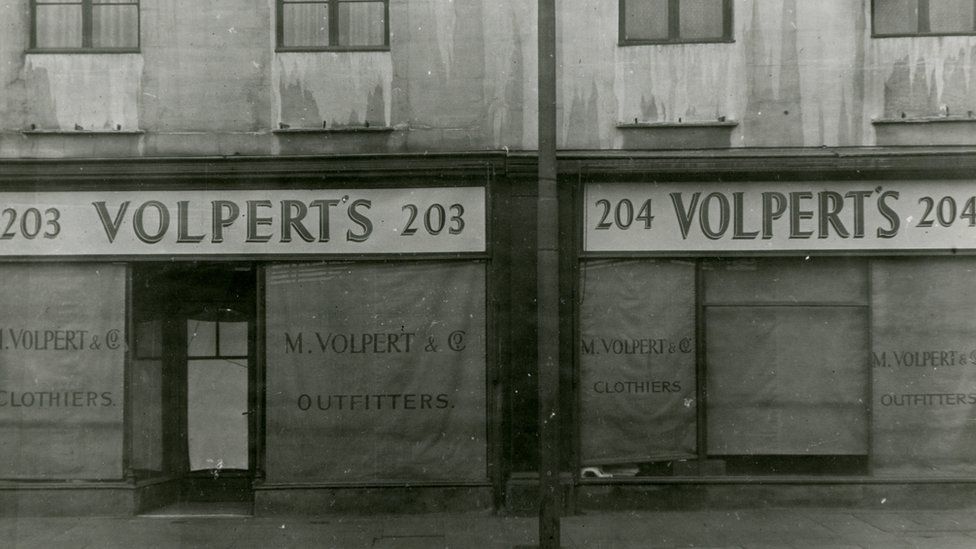

Detectives from Cardiff City Police, which is part of the now South Wales Police force, investigated the brutal killing of Ms Volpert inside her family outfitters and haberdashery shop in the docks area of Cardiff on 6 March 1952.

The well-known 41-year-old businesswoman had her throat cut while her mother, sister and niece were in the next room of the property in Cardiff’s old Tiger Bay area.

There was no forensic evidence and, despite having alibis backed by numerous witnesses, Mr Mattan, was arrested within hours of the murder, charged and convicted by an all-white jury.

Feeling of prejudice towards Mr Mattan, who spoke very little English, was heightened during his three-day trial at the Glamorgan Assizes in Swansea when his own defence barrister called him a “semi-civilised savage”.

Within six months of the murder, the 28-year-old was executed by infamous hangman Albert Pierrepoint at the gallows at Cardiff prison on 3 September 1952.

His widow Laura only found out he had been hanged when she went to visit him in jail – a few hundred yards from their home in Davis Street – and discovered a notice of his death pinned to a door.

“Even to this day we are still working hard to ensure that racism and prejudice are eradicated from society and policing,” said Mr Vaughan.

“Police investigations would have been totally different then and a long way off today’s excellent investigative standards.

“Even when reflecting on a case from 70 years ago, we do not forget those who have been affected by miscarriages of justice and we do not underestimate the impact this has on individuals.”

Relatives say the 46-year fight to clear the name of Mr Mattan, the last innocent man in Wales to be executed, “took its toll” on his family.

“My sons and I have not lived. We have simply existed,” Mrs Mattan, who died in 2008, once said.

Middle son Omar was just eight when he heard what happened to his dad and described that knowledge of being like a “cancerous growth” in his head. He said it changed his outlook on life and his behaviour.

“I think he struggled all his life. I know he was very angry,” Tanya Mattan, Omar’s daughter, told a new BBC Sounds podcast about the case.

Omar was found dead on a remote Scottish beach in 2003, aged 53, with a half drunk bottle of whisky next to his body.

“He grew up very angry at the world, I guess because of what happened. It never should have happened, he should still be here, living his life and watching his grandsons grow up,” added Ms Mattan.

“Whilst I am happy that an apology has finally been acknowledged, it seems it’s only been prompted by the upcoming podcast and so feels insincere.”

Tanya’s cousin Kirsty, daughter of Mr Mattan’s youngest son Mervyn, said the trauma of what happened to their father and the 46-year battle to clear his name affected them.

“It’s not just one life they took, three sons went through the stigma of their father being a murderer,” added Ms Mattan.

“My dad was a great man, our pillar of knowledge and strength. But they were all in dark places, they all abused alcohol and sadly died from it.

“It affected them mentally. My dad felt the loss of his father, it took its toll and they all died young.”

The legal team that represented the Mattan family at the Court of Appeal claimed he had been the victim of institutionalised racism as vital evidence to his case was not made available at his trial.

Leading human rights barrister Michael Mansfield, who represented the Mattan family at the Court of Appeal, said with the Black Lives Matter movement this case is “very pertinent right now”.

“Defendants who were non-white were in a worse position,” Mr Mansfield, who was also involved in the Birmingham Six and Stephen Lawrence cases, told the Mattan: Injustice of a Hanged Man podcast.

“If anything played a part in this case, it was anti-Somali – they would have been seen as intruders in south Wales – taking our jobs, our homes, they shouldn’t be here so get them off the street.

“And a jury listening to this case, looking at him thinking ‘he’s one of a number and if he didn’t do it, one of his mates did’ – it’s that kind of ethos.”

Mr Mattan, originally from Hargeisa in what was then known as British Somaliland, was one of thousands of seamen from overseas that made Cardiff docks their home after settling in the UK following World War Two.

A year after arriving in Wales, he married local girl Laura in 1947. But such was the prejudice and opposition towards their interracial marriage, the young couple were forced to live separately on the same street.

“People thought he was cheeky because he was British Somali and he wanted to be British and live British,” Laura once recalled.

“He loved everybody and thought everybody loved him. He just didn’t know the hostilities all around us.”