The farming industry spends tons of money on artificial means of reinvigorating soil, but an all-natural solution may already exist: beneficial microbes that have evolved to thrive in extreme environments. Puna Bio, which raised a $3.7 million seed round, captures and cultivates these extremophiles, putting them to work in milder climates where their plant-aiding processes work in overdrive — no genetic modification necessary.

It’s kind of a rule in the world of biotech that whatever you’re trying to do, nature already does it, and probably better than you ever could. So although we have seen modified microbes being put to work in agriculture, it’s more of an augmentation of their existing, near-miraculous ability to provide growing plants with crucial nutrients. And Puna’s thesis is that modification is superfluous with the right organisms.

“Our extremophiles are used to living with a low amount of nutrients; they have evolved, for around 2.5 billion years, to optimize nutrient uptakes such as nitrogen or phosphorus,” explained co-founder and CEO Franco Martínez Levis on behalf of his team. “For some properties, they show novel genes, or in other words, novel biosynthetic pathways. For others, the number of copies of the genes is higher compared to a non-extremophile microorganisms, which makes their activity more efficient.”

Multiple copies of a gene can amplify the natural processes these microbes already get up to — something that fellow microbial agriculture startup Pivot Bio showed with its modified organisms. In this case, however, there isn’t even the need to activate latent genes or tweak the processes. These critters already operate at peak performance, reliably producing nitrogen, phosphorus, or performing other tasks at rates or under conditions that local microbes balk at or tire out quickly in. This means even depleted soil can host happy bacteria, since they’re used to even more difficult climates.

“What we found is like what happens when an athlete trains at high altitude,” said Levis. But for these bacteria (though archaea, fungi and yeasts are also present in their collection) there’s more than just thin air to build their character. For instance, an organism that has evolved to live happily in briny, mineral-rich waters will be different from one that lives in a super-dry high-altitude desert — like “La Puna” in the Andes, after which the company is named.

A stromatolite, or biologically deposited minerals, and an aerial photo of the location where it was found.

“They’re very hard to isolate,” noted Levis. “You have to go 4,000 meters above sea level, you have to know the exact right place and time — you don’t just need scientists, you need adventurers. We have a big advantage in that one of my cofounder has published more than 150 papers on extremophiles — a lot of places where we’re finding these, she found them. She gets invited to prospect different places around the world.”

That co-founder is Elisa Violeta Bertini, who performs these bioprospections in various locations, most recently Utah’s Great Salt Lake, to locate and isolate interesting new microfauna. Under an international agreement called the Nagoya Protocol, organisms found and researched in this way gain something like an patent, allowing the institution, hosting country, and researcher to use them exclusively. So Bertini (and the two other cofounders, Carolina Belfiore and María Eugenia Farías, all PhDs as it happens) has been working with universities and research organizations across the globe to not just write tons of papers about these fascinating organisms, but to add them to Puna’s library of useful microbes.

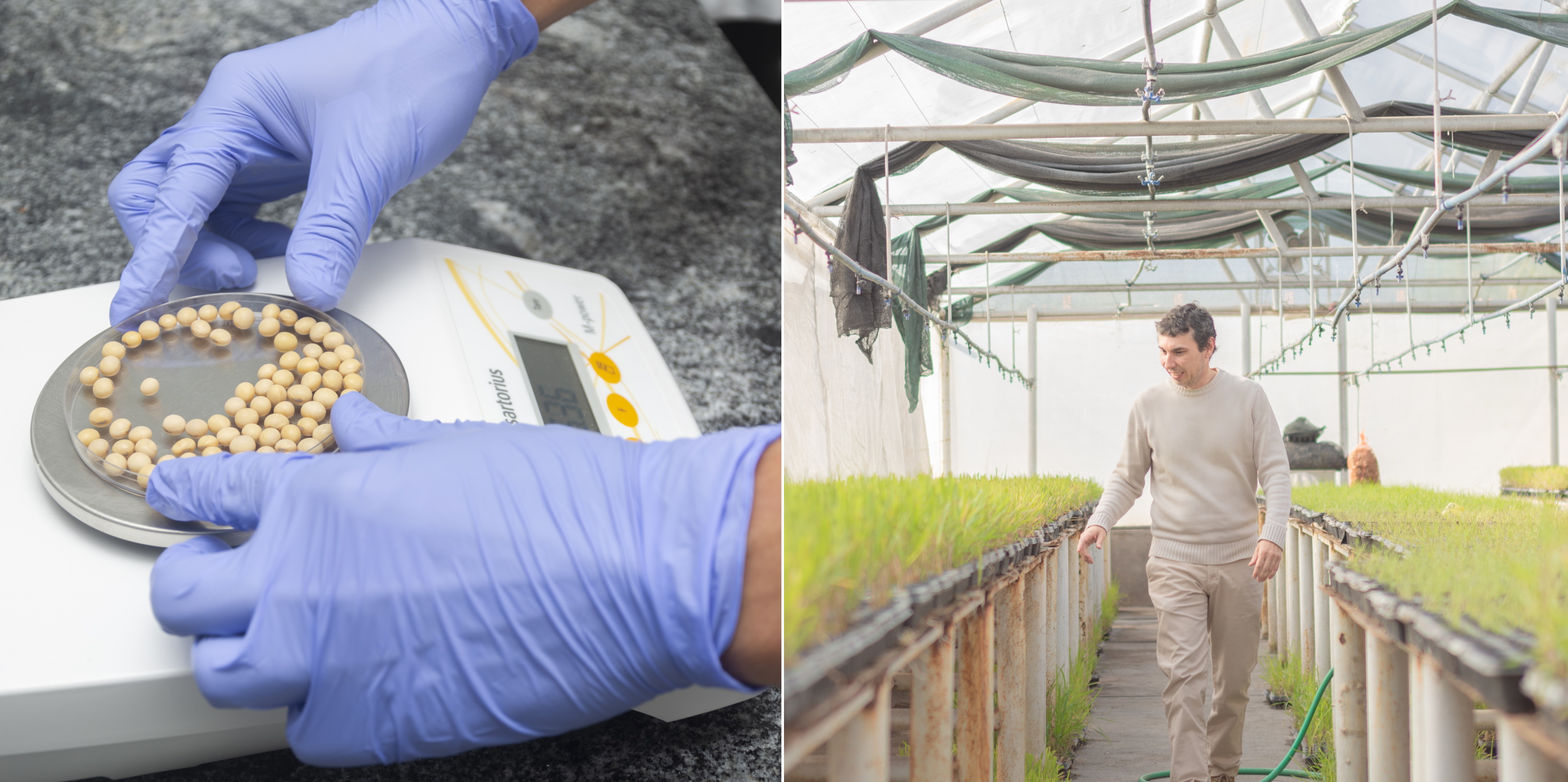

Levis was quick to add, though, that they do more than sprinkle bacterial fairy dust on crops. The company has developed and actually patented the method of cultivating, combining, and applying these special strains to seed stock.

A Puna Bio employee weighs seeds, left, and another examines seedlings in a greenhouse.

This comes with two important assurances: first, farmers don’t have to change the way they buy, plant, or treat seeds. Especially in the U.S., where farmers frequently buy stock pre-treated, Puna has been careful to make sure that everything works just as it did before.

And second, these extremophiles aren’t going to take over and outcompete the existing and perfectly benign microbes already present in the soil.

“What we actually found in some of our trials was synergies between these [i.e. native or commonly used] beneficial microbes and the addition of our microbes,” Levis said. “You’re really putting a very small microbe population into the soil, and because they stick very close to the plant it doesn’t really affect the rest of the population.”

There they are – the bacteria in question, nestled among the microscopic crenelations of a root fiber.

It does seem intuitive that a bacterium that produces free nitrogen or phosphorus under one set of soil and climate conditions might do so totally differently from how another bacterium does in totally dissimilar conditions. So the two types of organisms can combine and perhaps even synergize their effects when functioning simultaneously.

The $3.7 million seed round was led by At One Ventures and Builders VC, with participation from SP Ventures and Air Capital, as well as existing investors IndieBio (SOSV), GLOCAL, and Grid Exponential.

Levis said the first move the company will make with this cash infusion is launching their soybean treatment in Argentina, then expand to Brazil and the U.S., which between the three account for 80 percent of the market. The company will also be investing in further R&D (there are plenty more microbes to test out) and new facilities, including on in North Carolina. They hope to bring their approach to wheat and corn, bringing unmodified crops up to the performance levels of GM strains.

DUOS